Logging has been a vital part of Wisconsin’s history since before statehood, and the life of the lumberjack remains a vivid element of Wisconsin folklore.

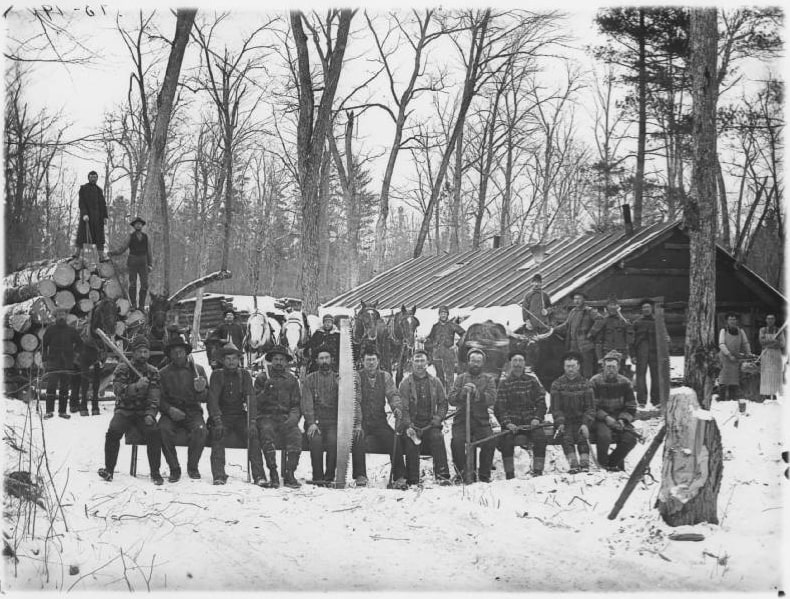

Establishing a Logging Camp

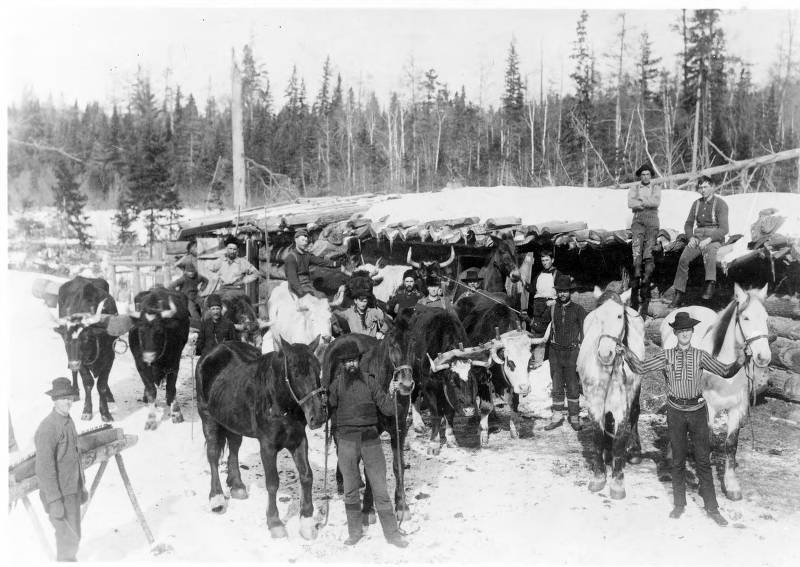

Most logging crews in Wisconsin operated only in the winter, taking advantage of hard, frozen ground to haul heavy loads of logs on sleighs rather than wheeled wagons. Establishing a winter logging camp involved much preparation: timber rights were acquired; timber cruisers estimated the volume of timber by species; supplies, sleds, tools, and food (for both people and animals) were purchased and hauled in to the work site; a work force was hired; dams for river log drives or railroad spur lines were constructed; and finally, bunkhouses, mess halls, and other buildings were erected.

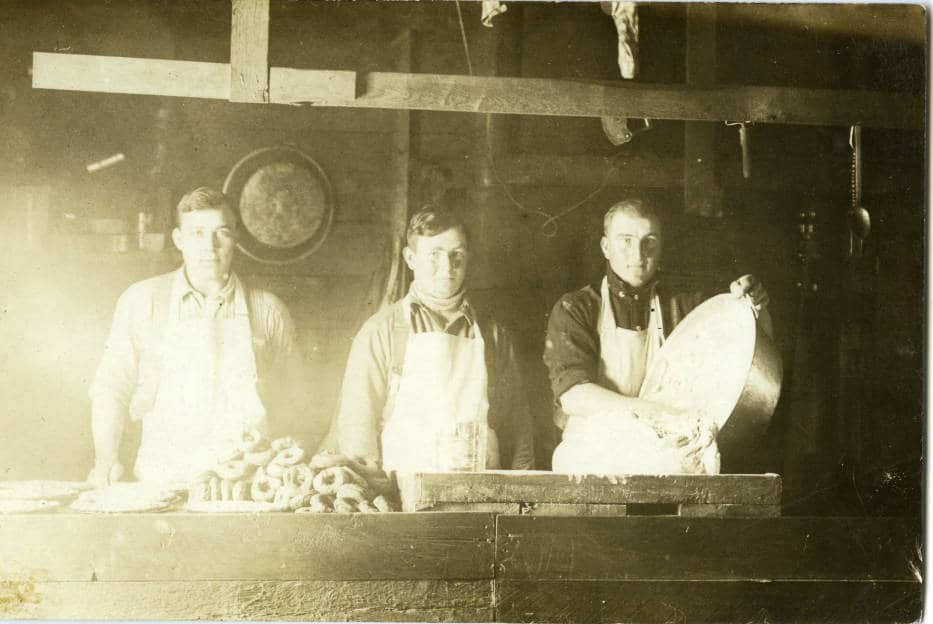

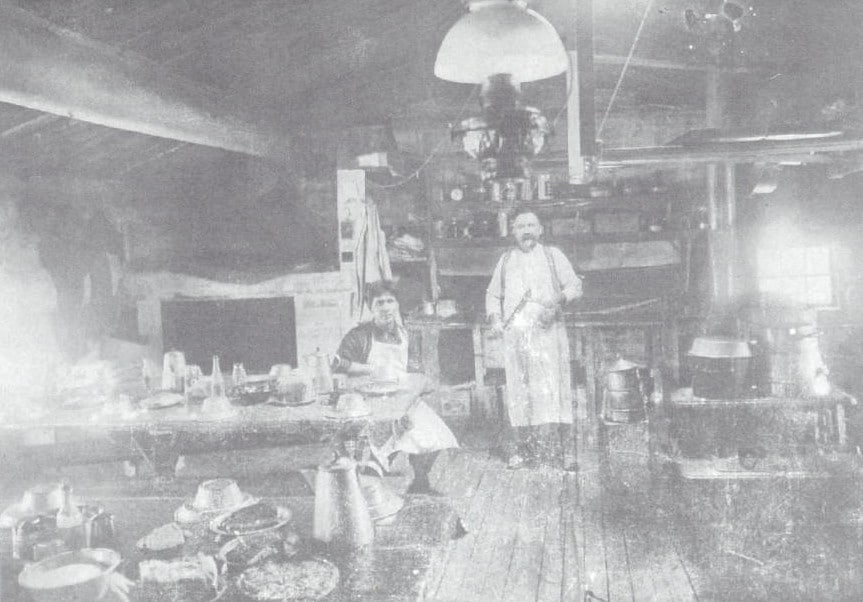

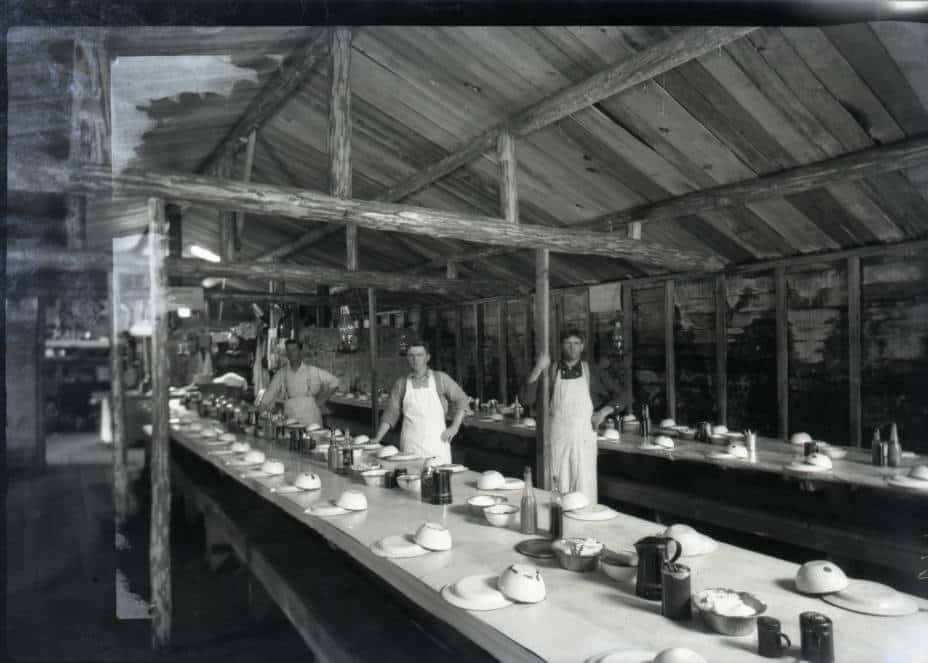

Keeping the Lumberjacks Fed

Written histories of lumber camp life often focus on food, as it was a monumental task to keep well-fed a hundred or more hungry men who engaged in heavy physical labor in cold, wet weather for more than 12 hours a day. In his book 100 Years of Pictorial and Descriptive History of Wisconsin Rapids (1934), T. A. Taylor describes a typical menu:

In the early camp days the main bill of fare was salt pork, navy beans, and flour. Molasses was added and later dried fruit especially prunes. ‘Flapjacks’ were a luxury and a special inducement offered the men. Coffee and tea and sugar finally found their way as the competition between camps grew stronger. The camps that were in active operation in the early nineties and later served meals that would rival any good hotel. Pie, cake, doughnuts appeared on the breakfast bill and fresh meats served in many forms three times daily.

Dinner (that is, lunch) was served in the forest while the men were working. Historian Malcolm Rosholt describes breaking for meals in the cold of the northwoods in The Wisconsin Logging Book 1839-1939 (1980):

The food was brought out to the crews in a compartmentalized container strapped to the back of the lunch carrier, or hauled out in a single horse sled. The lunch carrier built a fire to warm up the tea or coffee, but the food, which was supposed to be hot, often froze, not because it was not hot, but because the tin plates the food was served on were ice cold. To keep ahead of the cold, the men ate fast, standing up, or seated on a windfall. There was no hour off for lunch, but twenty minutes at the most with scarcely time for a smoke.

Supper, served in the mess hall back at the camp, was usually potatoes and gravy, fresh meat (if available), salted beef, pea soup, prunes or dried apples, fried cakes, rice pudding and tea or coffee.

Work in Camp

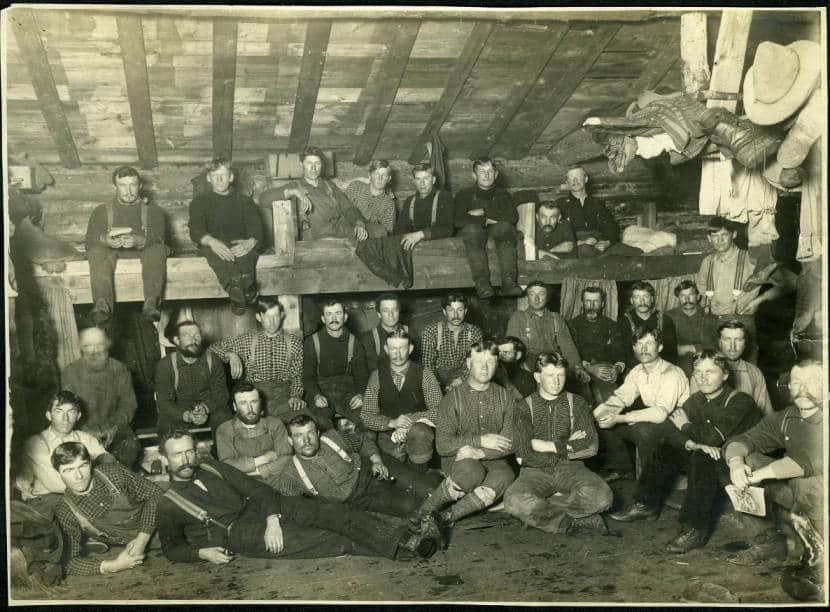

The work day did not end with supper. In the evening, the crew sharpened the saws, repaired the paths for skidding, and dried their clothes. Then the loggers might gather in the bunkhouse to play music or exchange stories while they repaired equipment or mended socks and mittens.

Time spent caring for animals was a major part of lumber camp life, as horses and oxen were the power sources that kept the logging operations running. Rosholt writes:

Each teamster curried his own horses, fed and watered them. This was almost a sacred rite because the teamster took pride in the appearance of his horses, argued about them, and lied about how smart they were.

A folk ballad called “Little Brown Bulls” immortalizes the work of these valuable animals. The lyrics describe a contest in a northwoods Wisconsin logging camp between a pair of “big spotted steers” and two “little brown bulls” to determine which team could haul or “skid” the most timber in a single day. The Wisconsin Folksong Collection from the University of Wisconsin-Madison includes a dozen recordings of this song as sung by former lumberjacks; each singer places the event in a different location. In Robert Walker’s version, the contest takes place in a logging camp on the Wolf River.

Days Off

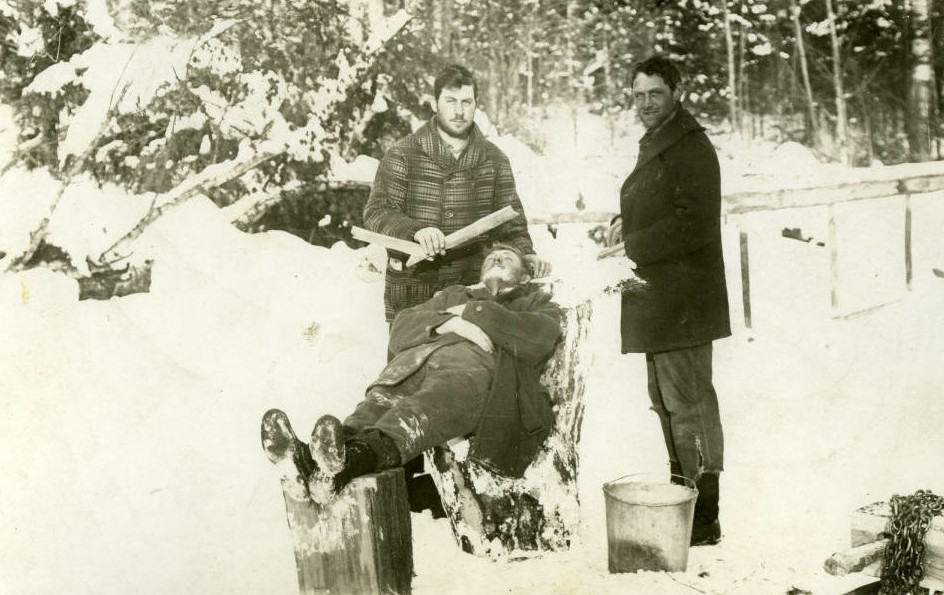

Sunday was the loggers’ day off. That meant laundry day, when the lumberjacks could wash and disinfect their clothes in pots of boiling water. Some took the opportunity to bathe and shave themselves as well.

Visitors often arrived in camp on Sundays — itinerant preachers, traveling salesmen, friends from a nearby camp, or lumber company officials. Sundays were also the best days for photographers to visit, and many of the surviving photographs from lumber camps were most likely taken on Sundays, according to Kathryn W. Kennedy in her paper “The Iconography of the Chippewa Valley Lumberjack 1869 to 1913” (1983).

Sources

The images in this online exhibit come from the following digital collections. Click the links to browse the full collections.

- Eau Claire Area Historical Photographs, Chippewa Valley Museum

- Eau Claire Area Histories, L. E. Phillips Memorial Public Library

- Langlade County Historical Society

- McMillan Memorial Library

- Stone Lake Area Historical Society

- Wisconsin Folksong Collection, 1937-1946, Mills Music Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Wisconsin Historical Images, Wisconsin Historical Society

Further Resources

- Kathryn W. Kennedy, “The Iconography of the Chippewa Valley Lumberjack 1869 to 1913” (1983)

- “Logging and Forest Products,” Turning Points in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society

- Malcolm Rosholt, Lumbermen on the Chippewa (Rosholt House, 1982)

- Malcolm Rosholt, The Wisconsin Logging Book 1839-1939 (Rosholt House, 1980)

- Ruth Stoveken, “The Pine Lumberjacks in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Magazine of History vol. 30, no. 3 (1947)

You must be logged in to post a comment.