by Elizabeth Feucht, UW-Milwaukee School of Information Studies

This spring semester, I’ve had the privilege of working with the Recollection Wisconsin Digitization Initiative and Menomonee Falls Public Library to digitize an array of objects from the Maude Shunk Local History Room Archives. These included ledgers, reports, a scrapbook, and other ephemera produced by the (erstwhile) Woman’s Club of Menomonee Falls and the Menomonee Falls Fire Company No. 1, mostly dating to the early 20th century. Read more about our fearless, trailblazing first librarian, Maude Shunk!

Not only was this fieldwork experience my first Official Real Life Digitization Project, it was also a sojourn into my own local history! I grew up in Menomonee Falls. I live here now. And, as T.S. Eliot once said,

“the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

Even through the act of digitizing these local history records (for preservation and access, via the MFPL digital collection), I’d like to think I arrived where I started and got to know it better than before, and even got to participate in it a bit. History is a collective process of memory-making, and local history provides a bridge by which people, locals, can tie their own, very personal experiences of a place to that place’s collective memory. To paraphrase from Carl Sagan a little: Local history is a way for locals to know themselves.

Throughout these pontifications, you have probably been wondering: Well, Elizabeth, what sort of scandalous, sensational, National Treasure-esque secrets did you unearth from these historic documents? The answer is: Not much of that, I fear. Among these objects, you will encounter the paraphernalia of mundanity: meeting minutes, budget sheets, annual reports—the kinds of documentation upon which societies are built. In fact, the oldest written records on Earth are financial and administrative records from ancient Sumer, inscribed some 5,000 years ago on clay tablets, which I’m sure would be cumbersome to scan. You may find them familiar. You may even have transcribed meeting minutes or prepared budget sheets yourself, for work or as a member of an organization. These kinds of records remind us of how humans, across space and time, are more alike than we are different—that humans have always been humans, and have often found a need to take to account the things which matter to us, the things which ought to be preserved for posterity, from the artistic to the utilitarian.

They also remind us of how we’re different, and how customs and the minutiae of our lives change over time. Woman’s Club gatherings, for instance, often opened with a song! And do you remember the last time you performed in a one-act play at a meeting?

An excerpt from the Menomonee Falls Woman’s Club meeting minutes for February 7, 1924.

My favorite pieces among these records, though, are the marginalia. These are the little handwritten notes, scribbles, and doodles inscribed at the margins of the official text (sometimes literally, sometimes figuratively). For example, the 1926-27 Woman’s Club Year Book shown below is exquisitely annotated with corrections and other reminders.

Pages from the 1926-27 Year Book of the Woman’s Club of Menomonee Falls.

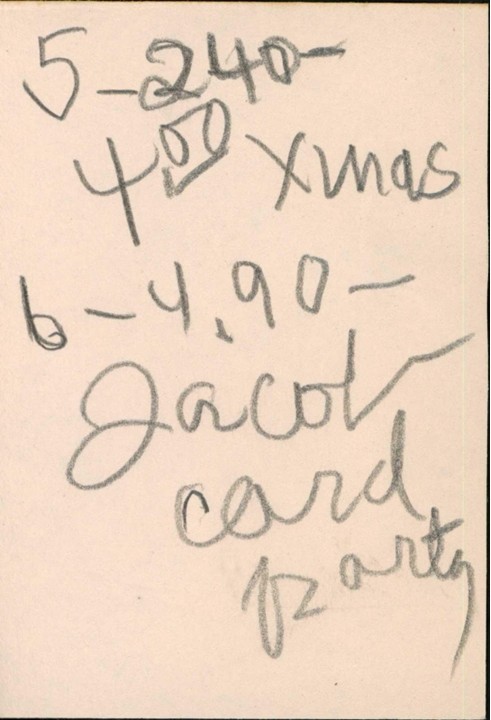

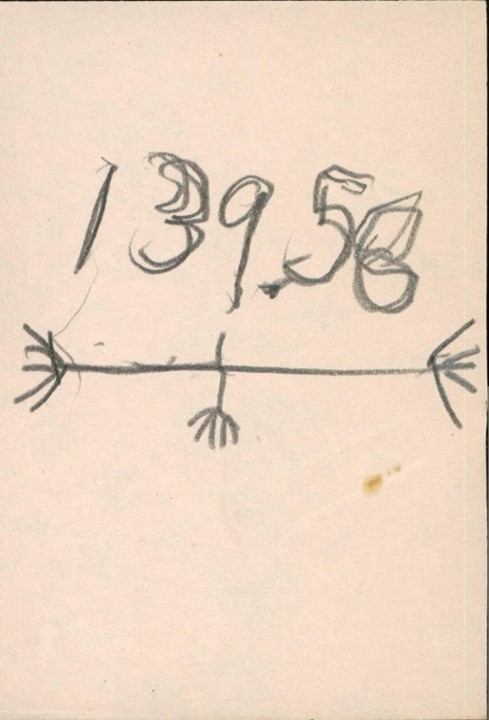

The budget sheets binder contains several scribbled notes, which undoubtedly served some purpose to the writer that I can no longer discern.

On the flyleaf of the Fire Company’s 130-year-old ledger book, someone seems to have sketched the layout of a building, possibly the fire station.

A sketch of a building layout inscribed in the Menomonee Falls Fire Company No. 1 ledger book.

These peripheral inscriptions divulge, I think, a sort of vital, intimate sense of whoever was holding the pencil. It’s a sense we can embody. We can imagine ourselves, even, at a writing desk or a table or a countertop somewhere, one hand splayed over the page or maybe propping up our chin, the other closed around a pencil, scribbling something urgently or boredly or purposefully, in characters and drawings not carefully constructed but quick and authentic—a tangible, recognizable echo of some singular person, their singular handwriting, lingering from the past into the present. In these odd marginalia of yore, too, we can discover the local.

But one of the most important things about the Maude Shunk Local History Room is that it’s open to the public! Library patrons can use the very same scanners that I used to digitize their own records, peruse genealogical resources, and even volunteer with local history preservation efforts. We are all complicit in the creation of history, and we all have the power to participate.

For more information about the Recollection Wisconsin Digitization Initiative, visit https://recollectionwisconsin.org/rwdi.

You must be logged in to post a comment.