By Elisabeth Joy Primrose (UW Milwaukee SOIS) for Recollection Wisconsin

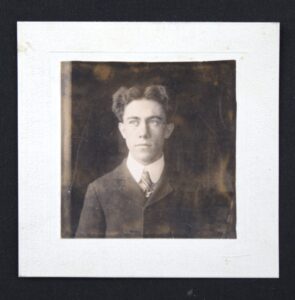

This summer, Recollection Wisconsin partnered with the Tomah Area Historical Society and Museum (TAHSM) to digitize and provide online public access to materials from the Frank O. King Collection. Frank O. King (1883-1969) was an award-winning American cartoonist best known for creating the comic strip Gasoline Alley. TAHSM’s Frank O. King collection of sketches and artwork offers extensive evidence of the early stages of King’s artistic career, showcasing a broad range of subjects. The collection contains portraits, comics, posters, ads, and decorative letterheads drawn by King throughout his career.

King’s witty social commentary and choice of subjects provide a wealth of historical context to the collection. Moreover, as illustrated through the selected examples below, King’s early illustrations reveal a perceptive and nuanced engagement with American social and political life, extending well beyond his later fame with Gasoline Alley. His sketches and comics reflect both admiration for public figures and a subtle critique of prevailing ideologies.

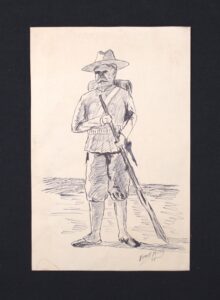

The first sketch is assumed to be a portrait of Theodore Roosevelt. This piece was drawn in 1898, the same year that Roosevelt joined the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, as part of the Spanish-American War effort. Soon after, Roosevelt was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and given command of the regiment, at which time it was nicknamed “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders”.

1898 was also the year that Roosevelt was elected Governor of New York State. It’s difficult to determine King’s exact motivation in drawing this sketch. However, the precision of the likeness reveals that news of Roosevelt and his heroic feats had travelled to rural Wisconsin and likely inspired the artist, who was only 15 at the time.

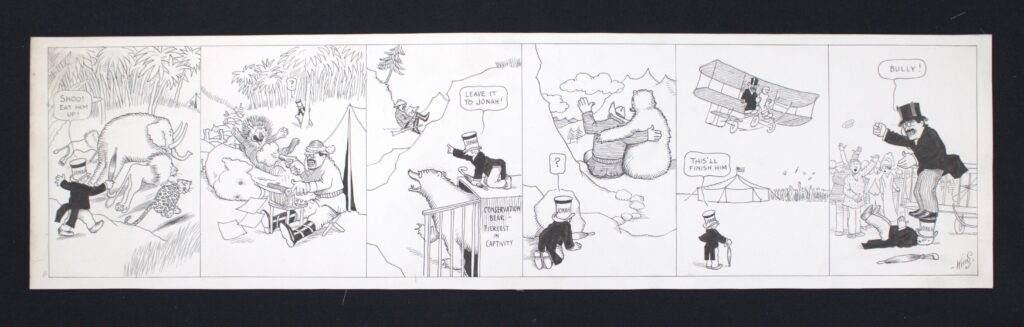

This second piece was created by King sometime around 1910, at the beginning of his long career as a cartoonist for the Chicago Tribune. The Tribune was where King would later introduce Gasoline Alley. However, before Gasoline Alley, King had other recurring comic series. One such series was Jonah, a Whale for Trouble, where the main character, Jonah, served to expose other characters to trouble and poor circumstances. In the accompanying strip, King illustrates respect for Roosevelt by creating a storyline where he’s impervious to Jonah’s hijinks. Additionally, the strip celebrates Roosevelt’s contemporary accomplishments, including his African safari and resulting publications, his conservation efforts, and his ride aboard a Wright Brothers airplane.

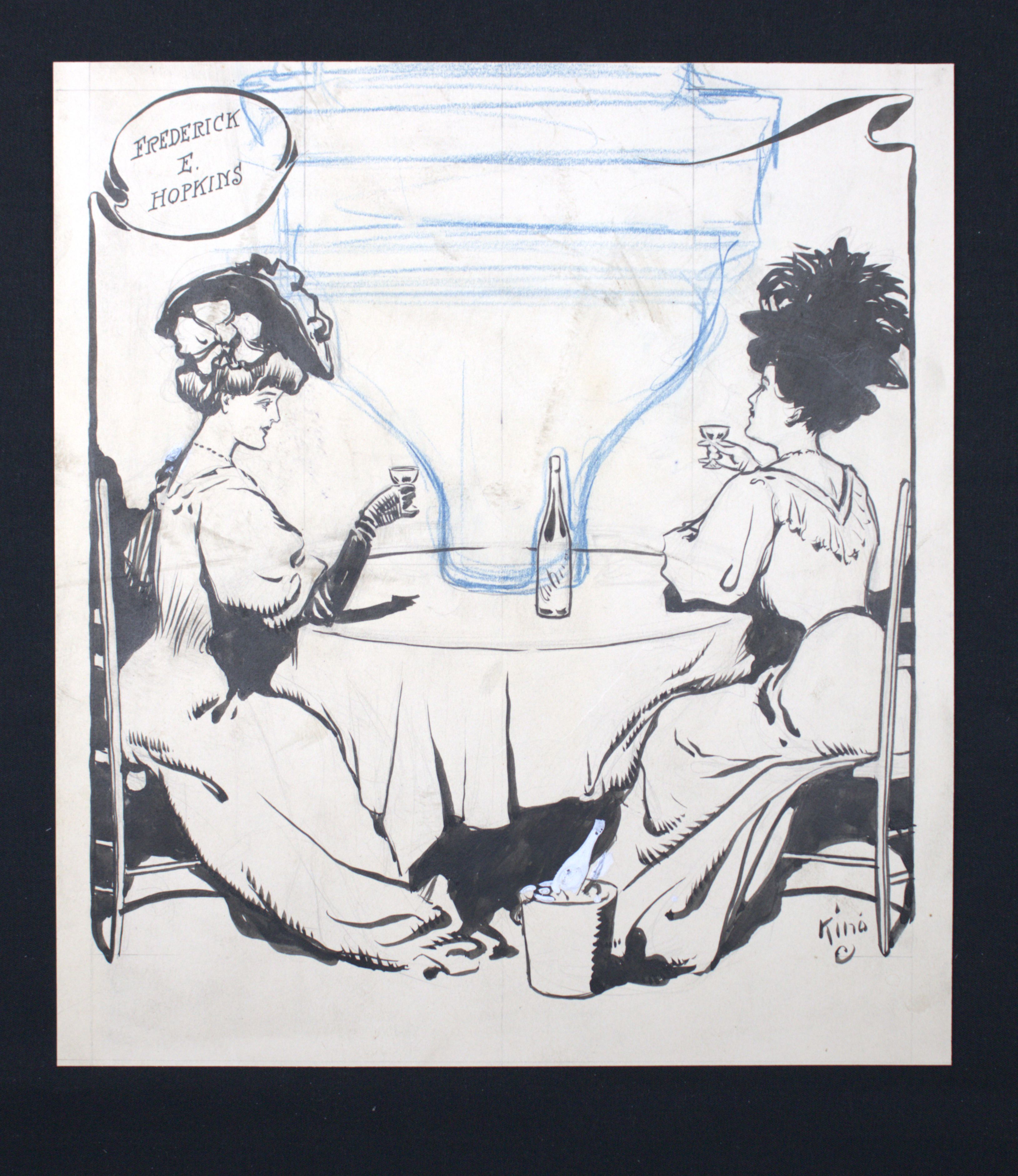

King’s social commentary deepens in this piece, created in 1907 while King worked for the Chicago Tribune. The name in the corner is that of Reverend Frederick E. Hopkins of Pilgrim Congregational Church. On September 2, 1907, Hopkins posted a placard on the church’s door announcing an upcoming sermon on “The Growing Habit of Women Drinking Booze in Public”. This began Hopkins’s month-long crusade against women drinking in public. Despite the drawing bearing Hopkins’ name, by portraying the women with dignity and poise, King challenges the alarmist tone of Hopkins’ campaign, offering a more progressive view of gender and public behavior.

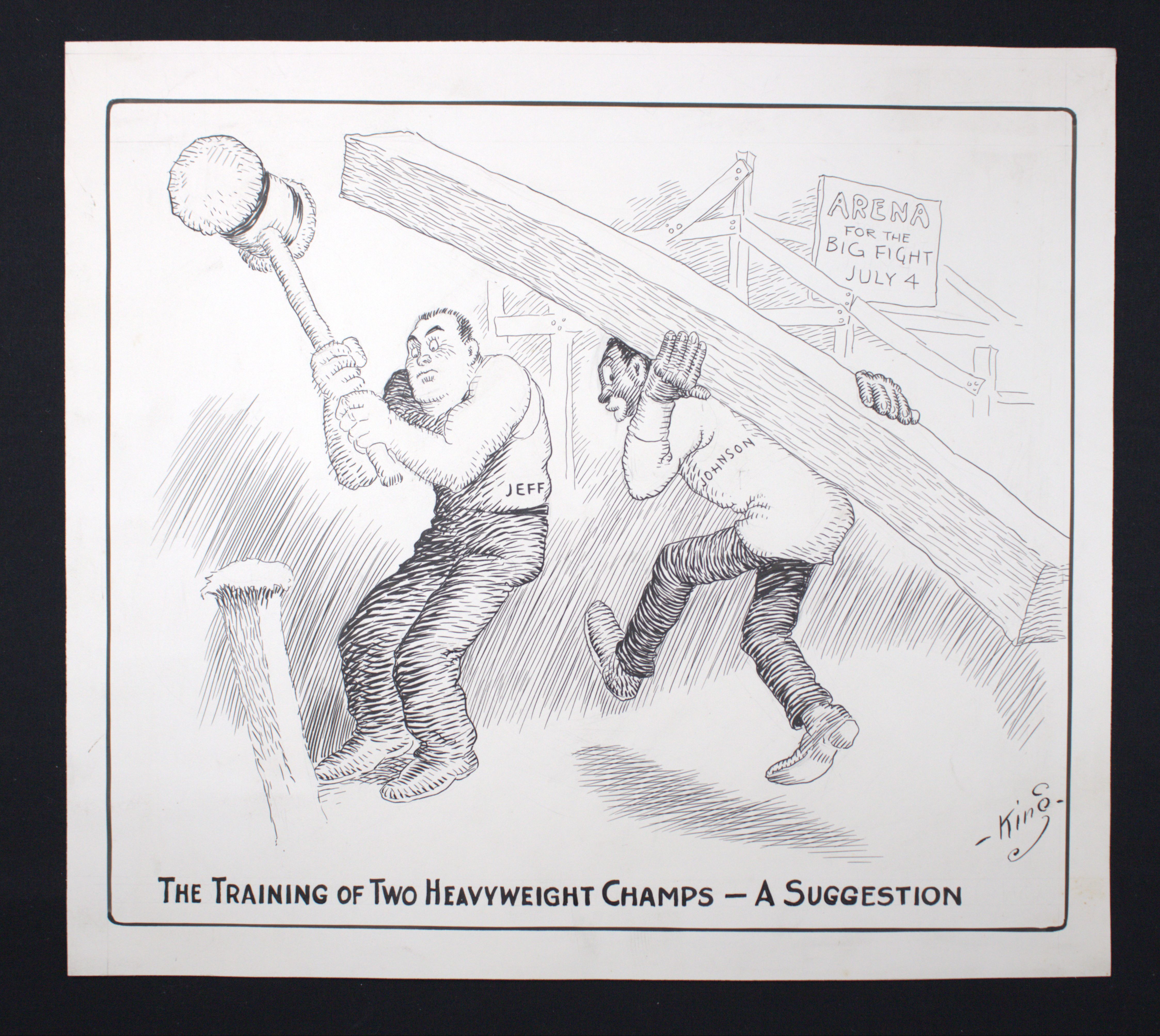

This last selection of images was created in 1910 to discuss the historical boxing match between Jack Johnson (1878-1946) and James J. Jeffries (1875-1953) that took place on the Fourth of July that year. Johnson became the first Black World Heavyweight Champion in 1907. In response, Jeffries, a previous World Heavyweight Champion (1899), amidst pressure from media, investors, and the public, challenged Johnson to a prize match to defend the title. The match, nicknamed the “fight of the century”, was highly anticipated, resulting in extensive media coverage. Due to the racial tensions of the time, many rooted for Jeffries victory in hopes that his win would support theories of white superiority. Additionally, the popular contemporary writer Jack London penned the nickname “the Great White Hope” for Jeffries.

In the first image, King suggests that the two competitors train for the match by constructing the arena where it will take place in Reno, Nevada. In this image, King not only throws his hat into the ring with the rest of the media giving the fight attention, but he also draws attention to the construction of the arena, itself a historical event. After all, the 22,000-seat arena was constructed by 300 men for the sole purpose of housing this fight. Before this, a boxing venue had never been built for a single fight.

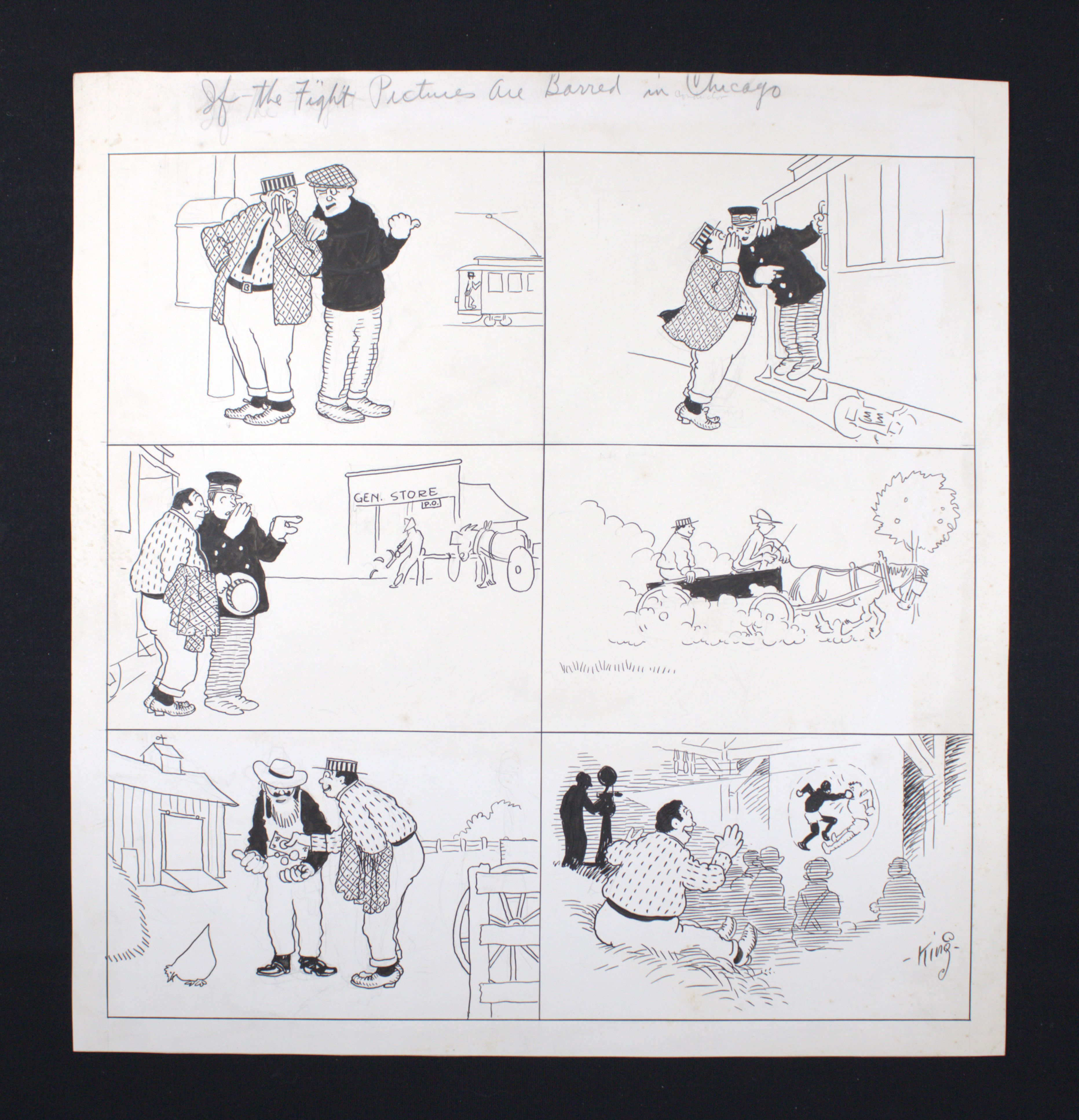

The second image humorously portrays the back-alley schemes that Chicagoans will commit to gain access to the film of the fight if it is banned from theaters in the area. Through this comic, King draws attention to calls to censor the fight of the century. Claims were made at the time against the legality of publicly displaying a prizefight since they were considered illegal in most states. However, most historians agree that the push for censorship of the Johnson-Jeffries fight was due to the racial tensions surrounding the event. However, most historians agree that the push for censorship of the Johnson-Jeffries fight was due to the racial tensions surrounding the event. The sad truth is that within two days of Johnson’s win, 10 Black people had been killed in six different states, the beginning of a series of violent race riots that would come to be known as the Johnson-Jeffries Riots.

Frank O. King’s early works offer a nuanced commentary on American social and political life, blending admiration with subtle critique. His 1898 portrait of Theodore Roosevelt reflects King’s awareness of Roosevelt’s rise as a national hero, while his Jonah comic strip celebrates Roosevelt’s accomplishments. Yet King’s engagement with politics is also critical, as seen in his 1907 caricature of Reverend Frederick E. Hopkins, which challenges his crusade against women drinking in public. By portraying women with dignity, King questions societal norms around gender and morality. King’s treatment of the 1910 Johnson-Jeffries boxing match highlights racial and cultural tensions, mocking the media spectacle and public obsession with white supremacy. Through these works, King both participates in and critiques the national conversation, revealing a sophisticated understanding of race, gender, and popular culture in early 20th-century America.

Elisabeth Primrose is a student intern working with Tomah Area Historical Association as part of the Recollection Wisconsin Digitization Initiative. For more information about this program, visit our website or contact vicki [at] wils.org.

You must be logged in to post a comment.