This exhibit was created in collaboration with Emily Nelson, an undergraduate History major at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

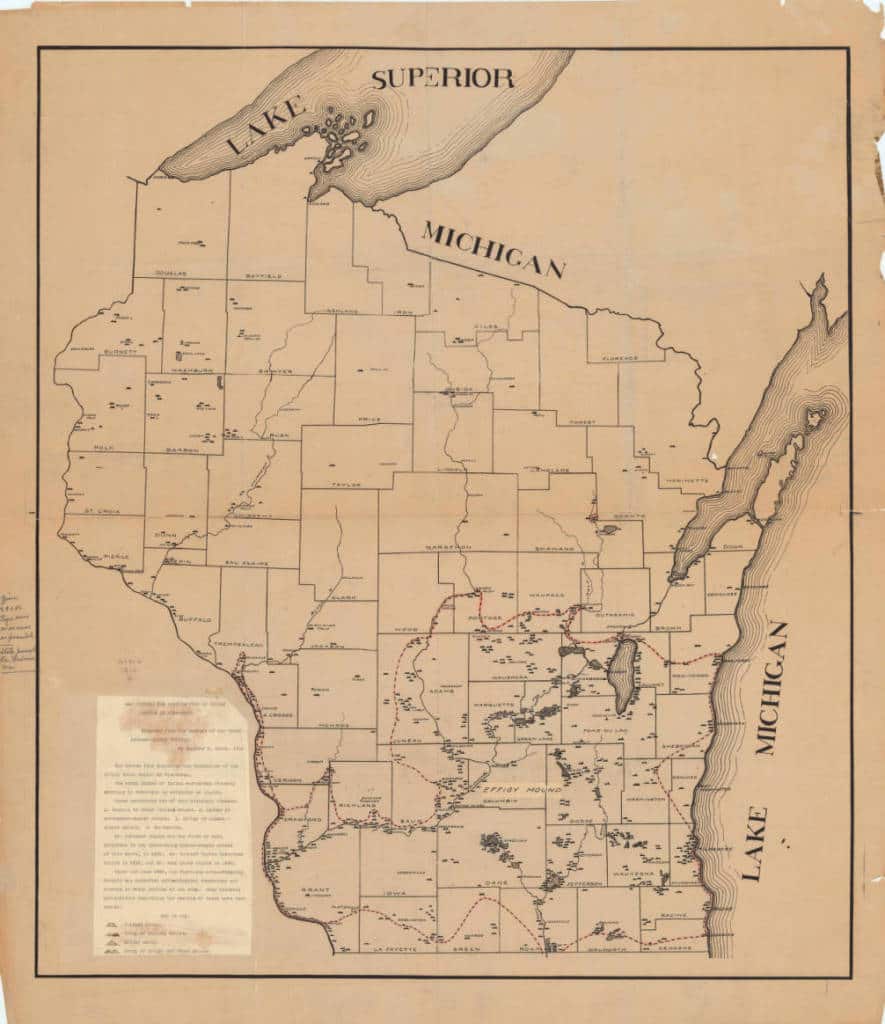

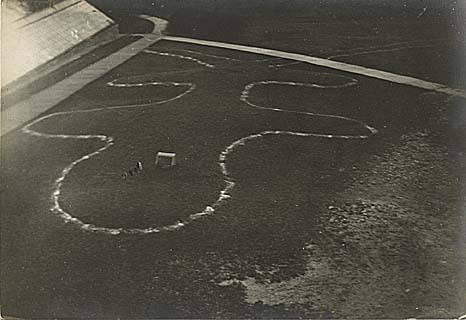

More than a thousand years ago, Indigenous people in southern Wisconsin sculpted the landscape into the shapes of the creatures they saw around them. These mounds in the earth continue to watch over the people of the state. A bear looked over 19th century miners digging for lead; a bird rests just feet from where students study on the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Observatory Hill today. These marvels have been well studied, recorded and visited, but much about them remains a mystery.

Effigy mounds are primary source evidence for reconstructing the lives of their creators. Radiocarbon dating has placed the people who built the mounds to have lived roughly between 650 – 1200 C.E. Archaeologists believe that effigy mounds came after Hopewellian-period conical and linear mounds, which were also built for burial and ceremonial purposes but are found mainly in the northern half of the state. Materials used to build the mounds and artifacts unearthed inside them give clues to the resources and culture of their creators. Most fascinating of all is how mound layouts demonstrate the social sophistication of the Late Woodland period in Wisconsin.

Early theories on the origins of the mounds were plagued with misinformation and prejudice against Native peoples. European and American observers did not believe that ‘savage’ persons could be capable of such intricate works of earthen art. The most popular theory of 19th and early 20th century researchers was that a ‘Lost Race’ created the mounds.

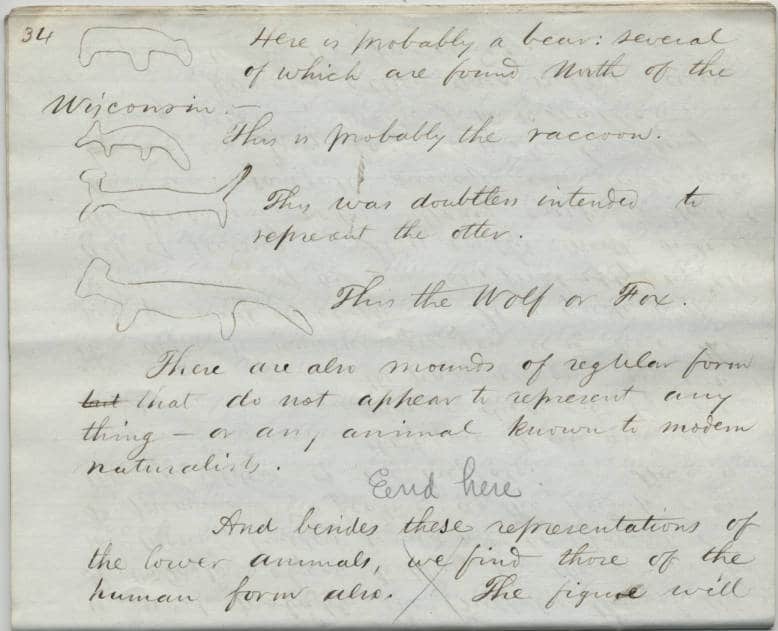

Increase Lapham, regarded as Wisconsin’s first great scientist, put the idea of the ‘lost race’ to rest by revealing that material evidence found within and around the mounds corresponded with surrounding Woodland tribal culture. Lapham focused on the mounds throughout his career, describing them in detail in his 1855 publication The Antiquities of Wisconsin.

Many of the mounds Lapham recorded and sketched have since been destroyed. In the 19th and 20th centuries, as much as 80% of Wisconsin’s mounds were destroyed by urban development.

Some mounds contain human remains and pottery pieces that indicate burial ceremonies. By examining the pottery, archaeologists have placed Middle Mississippian tribes as the mound artists. The pottery in the mounds demonstrates that a high level of trade and movement was occurring in the region: the clay was tempered with crushed shells traced to the center of Mississippian lifestyle, Cahokia, located in present-day southwest Illinois. Around 1000 C.E., it is believed that migrants from Cahokia traveled along the Mississippi River to settle in the southern half of Wisconsin. This corresponds with the location of effigy mounds. Around two-thirds of all effigy mounds are found in the southern half of the state. The Ho Chunk believe that it was their ancestors who built the effigy mounds and evidence of Woodland and Mississippian communication supports their claim.

Because they are constructed in the shape of animals, effigy mounds are thought to have been used in religious ceremonies. Native American symbols of the Spirit World are associated with animals. Oneota groups of the Upper Midwest (900 – 1650 C.E.) were separated into and symbolized by three clan systems: the sky clans (birds), the water clans (water panther, serpents), and the earth clans (man shapes, land animals).

Effigy mounds are often found in groups and were typically built in places that overlook rivers. Water too had spiritual significance for Native peoples of Wisconsin. In Ho Chunk oral tradition, the effigy panther tails point to underground springs, entrances to the underworld. However, some archeologists have challenged modern tribal connections since the designs of effigy animals do not match modern iconography.

The layers of a mound contain special soils and ashes which suggest ritual ceremony in their construction. In the Kratz Creek site in Marquette County, golden sands and brick red clay have been collected from local deposits and layered with fire-blackened charcoal and ashes. The layers suggest that repeated rituals would have taken place over time.

Some Ho Chunk tribes believe that effigy mounds were territorial markers and locations of place-specific rituals. Animals representing the different Ho Chunk clans (such as the bird, bear, and panther) were segregated to separate parts of the state. Around 80% of all bear effigies are located in southwest Wisconsin. More than 90% of all panther effigies are found in the southeast.

Mounds may have been used for seasonal gathering places of mobile bands. Wisconsin’s diverse climate necessitated movement across the seasons: using upland resources in the cooler months and aquatic ones in the warmer months. Ceremonies at a special location would have reaffirmed social relationships and alerted other tribes to territorial ownership. Mounds were not usually placed at village sites.

Today, approximately 4,000 mounds survive in Wisconsin, from the estimated 20,000 once present in the 1600s. It is our responsibility to protect them; state law prohibits mound destruction and disturbance without special permission. Thousands visit and study these monuments to uncover the lives of the people who built them. Theories of their function have varied, but what remains a constant conclusion is the architectural genius and historical significance of these impressive structures.

Sources

The images in this online exhibit come from the following digital collections:

- Edgewood College History, Edgewood College Library

- Logan Museum of Anthropology, Beloit College

- Maps and Atlases Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society

- Turning Points in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society

- UW-Madison Collection, UW-Madison Archives. Part of the University of Wisconsin Collection from UWDC.

- Wisconsin Historical Images, Wisconsin Historical Society

References and further reading

- Robert A. Birmingham and Leslie E. Eisenberg, Indian Mounds of Wisconsin (University of Wisconsin Press, 2000)

- Jon Kasparek, Bobby Malone, and Erica Schock, Wisconsin History Highlights: Delving into the Past (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2004)

- Patty Loew, Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2013)

- Nancy Oestreich Lurie, Wisconsin Indians (Wisconsin Historical Society Press)

- “Effigy Mounds Culture,” Wisconsin Historical Society

- Andrew Khitsun, “Wisconsin Mounds,” http://www.wisconsinmounds.com

- “Burial Mounds,” Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

- “Native Americans and the Preserve,” Lakeshore Nature Preserve, University of Wisconsin

You must be logged in to post a comment.