This feature is curated by Mark Speltz, senior historian for American Girl. Mark began exploring the photographic record of the civil rights movement in Milwaukee as a graduate student in public history at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. In the six years since, he has interviewed participants, politicians, and photographers and remains ever hopeful new photographs and stories will come forth.

During the 1960s, Milwaukee’s African-American community waged protests, organized boycotts, and fought legislative battles against segregation and discriminatory practices in schools, housing, and social clubs. For a comprehensive history of the struggle for civil rights in Milwaukee, see the March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project, developed by UW-Milwaukee students, faculty and staff. This digital collection features primary sources including photographs, unedited news film footage, text documents, and oral history interviews from the Milwaukee Area Research Center at the UW-Milwaukee Libraries as well as a detailed timeline and bibliography.

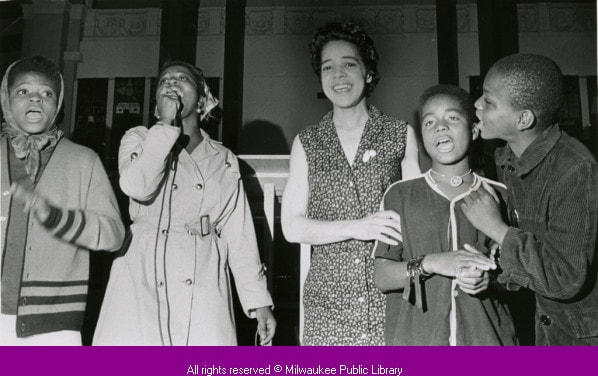

This well-known Milwaukee civil rights movement photograph features young members of the NAACP Youth Council and their advisor, Father James Groppi, proudly carrying the American flag. This march took place in Wauwatosa on August 28, 1966, exactly one year before the explosive open housing demonstrations began.

In 2012, activist Margaret Rozga identified several of the young men and women marching with her late husband, Father Groppi:

Unfortunately most of the people in the picture have died. The woman on the left is Carol Butler, the tallest person is Duane Tolliver. The person in the sunglasses behind Carol Butler may be Forthune Humphrey. The woman behind the two Youth Council men on the right (with her right hand up at her forehead) is Vada Harris.

To find out more about the early years of the NAACP Youth Council in Milwaukee, before the direct actions of the 1960s, see Erica L. Metcalfe, “Future Political Actors: The Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council’s Early Fight for Identity,” Wisconsin Magazine of History vol. 95, no. 1 (2011)

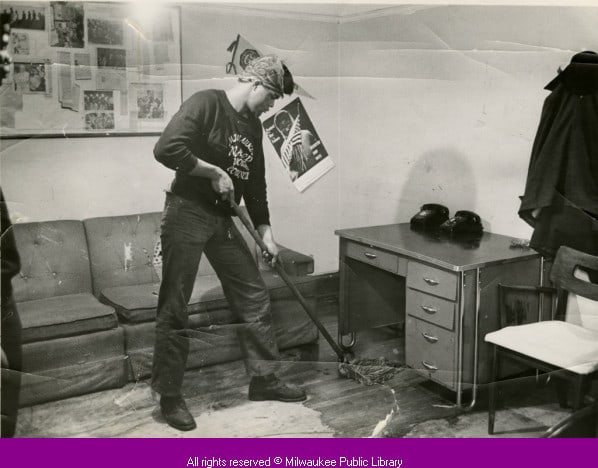

A close reading of this December 1966 photograph of a Youth Council member cleaning the group’s Freedom House reveals a bulletin board covered with news articles and photographs from the summer’s dramatic marches in Wauwatosa. The activists learned their confrontational approach, and the reactions it elicited, attracted heavy press coverage. They would continue to use this tactic in future demonstrations.

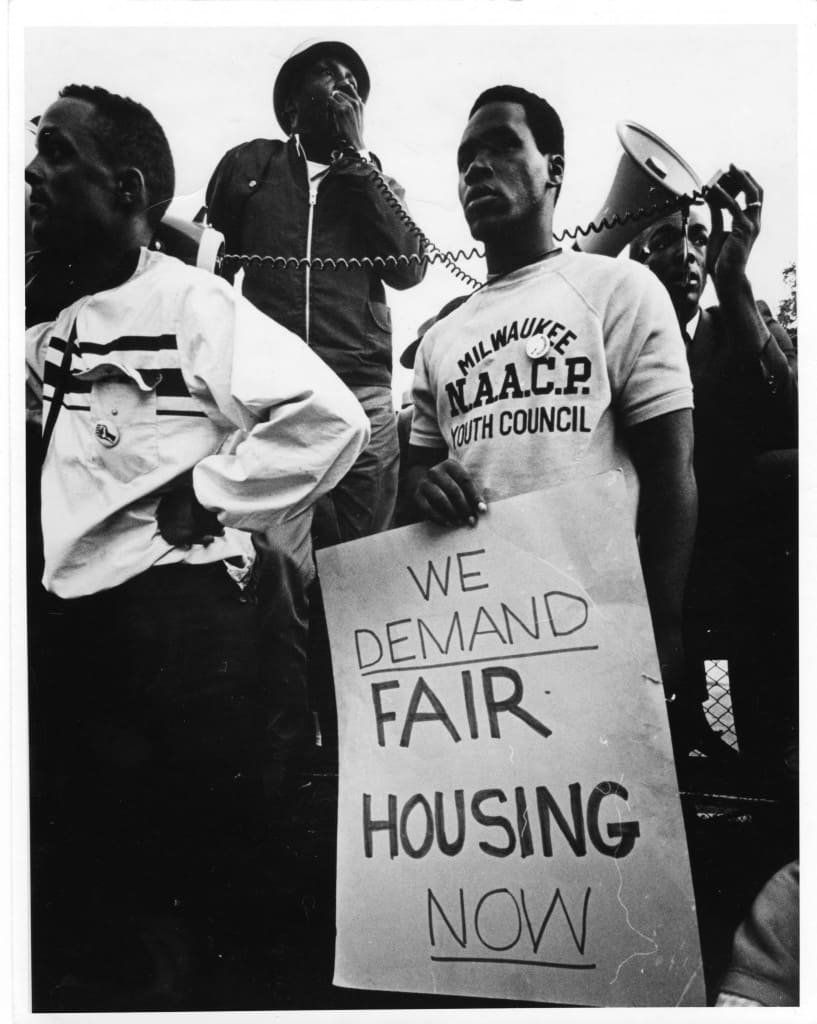

Milwaukee’s African-American residents faced blatant discrimination in housing, usually meeting with hostility or being refused housing altogether if they tried to leave segregated neighborhoods. Alderwoman Vel Phillips first introduced much-needed open housing legislation in 1962. After five years of casting the sole vote in favor of the legislation, she and the NAACP Youth Council joined forces and took to the streets to call attention to the need for open housing.

This eerie silent news clip captures the tense and edgy atmosphere as civil rights marchers made their way through Milwaukee’s south side in late August 1967. From the opening scene featuring lines of heavily armed police officers to a clip of a marcher praying with a rosary, footage like this was recorded and broadcast by WTMJ-TV for weeks on the evening news.

Learn more about events leading up to the 1967 fair housing demonstrations in Margaret Rozga, “March on Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Magazine of History vol. 90, no. 4 (2007). A timeline from the March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project documents the escalation of the demonstrations in late summer 1967.

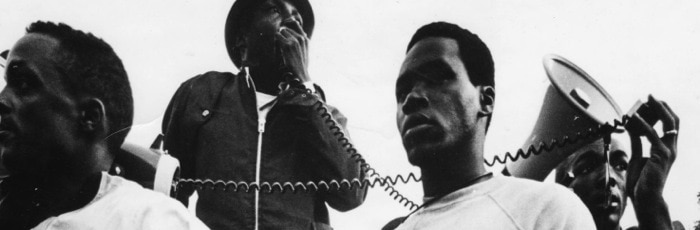

Well-known protest photographer Ben Fernandez came to Milwaukee on assignment, like many other photographers, as national news outlets took notice of the civil rights struggle unfolding in the urban north. Fernandez published this photo in his 1968 book In Opposition: Images of America Dissent in the Sixties.

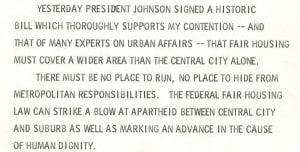

The NAACP Youth Council continued to march nightly on the streets of Milwaukee through the remainder of 1967 and into March 1968. Then, on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, sparking riots and demonstrations across the country. Congress quickly passed the Civil Rights Act (the “historic bill” mentioned by Milwaukee Mayor Henry Maier in his statement at right), which included strong open housing provisions. Milwaukee’s Common Council soon followed suit, enacting an ordinance to prevent racial discrimination in most housing in the city.

Sources

The images in this post come from the following digital collections. Click the links to browse the full collections.

- March on Milwaukee Civil Rights History Project, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries

- Milwaukee Historic Photos, Milwaukee Public Library

Learn more about the civil rights movement in Wisconsin

- Black Thursday online exhibition, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh

- Desegregation and Civil Rights, Turning Points in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society

- Patrick T. Jones, The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Harvard University Press, 2009)

You must be logged in to post a comment.