Guest curator, Joe Hermolin, is the Langlade County Historical Society president (a Recollection Wisconsin content partner) and Steering Committee member. Hermolin worked at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for many years in the Department of Biomolecular Chemistry in the Medical School. In retirement, he moved to rural Langlade County and developed an interest in the region’s history.

Introduction

When, on March 4, 1933 Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) was inaugurated as President, the United States was mired in the Great Depression with unemployment estimated at 25% and no social safety nets such as Social Security and unemployment insurance in place. He promised Americans a “New Deal” and stated that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” He immediately set out with an unprecedented series of proposals to use the federal government to get Americans working and to improve the infrastructure in rural and urban communities. What he later named “The first 100 days” became a benchmark of presidential achievement.

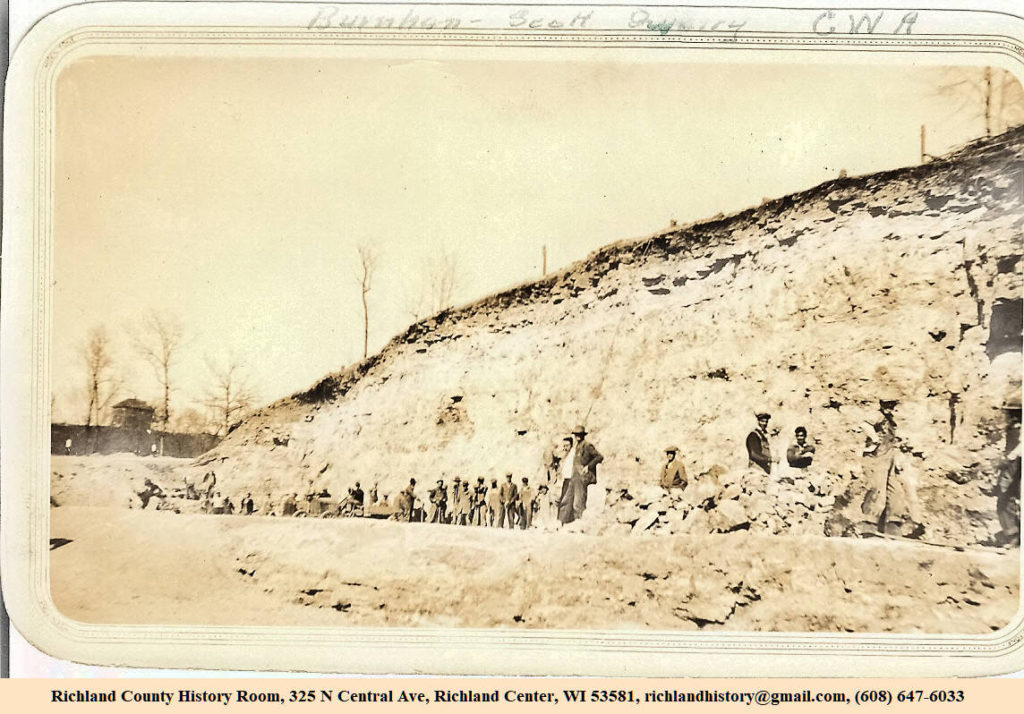

An alphabet soup of programs was initiated. One of the first was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It was accompanied by short term programs such as the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). Later, the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the reorganized, broadly encompassing Works Progress Administration (WPA) and many more agencies, covering infrastructure, conservation, recreation, education, and the arts were developed.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC)

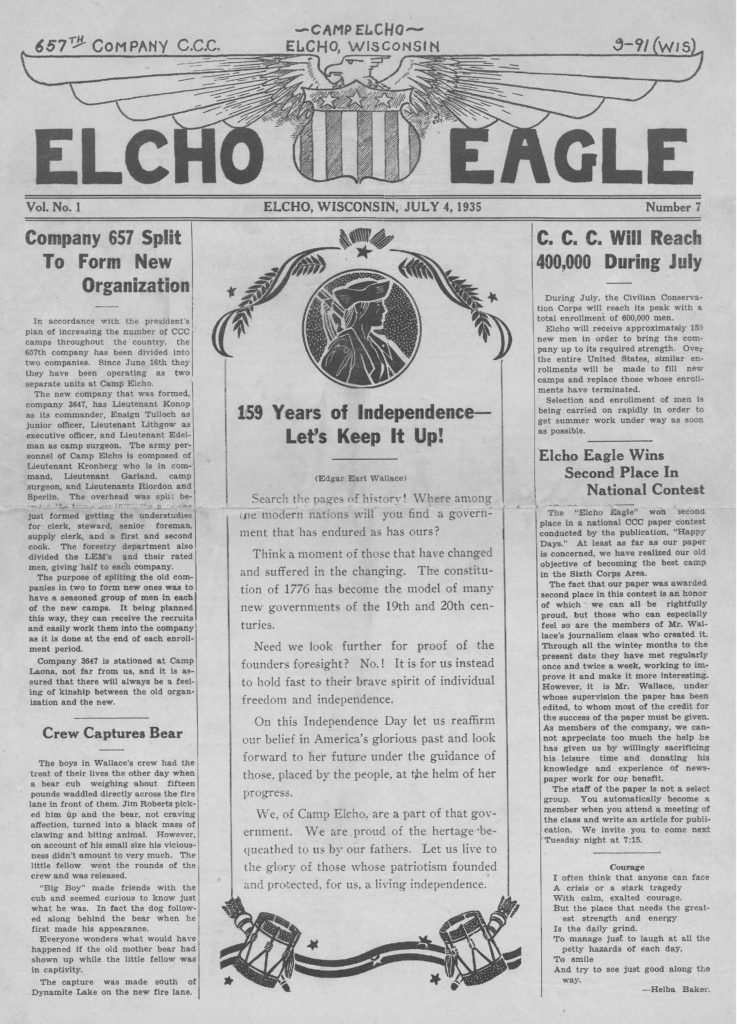

Less than one month after FDR’s inauguration, a plan for the CCC was developed, presented to Congress, and approved. CCC Camps operated in a military style under several departments including Labor, War, Agriculture, and Interior. The CCC existed from 1933 to 1942. Some camps ran only briefly, but by 1942 when the CCC was disbanded with U.S. entry into World War II, over 4,000 camps had been established nationwide. The peak years were in 1935-1936 with about 3,000 camps. Young men enrolled for six-month periods (renewable for up to two years). They earned $30 per month, $25 dollars of which was sent home to their families. For some families, the $25 per month meant saving the family farm. For several enrollees with no job prospects, it provided training and development of skills that would lead to employment in the private sector.

In northern Wisconsin, much of the efforts of CCC enrollees was directed toward reforestation of the “cutover,” repairing damage resulting from overharvesting by the lumber industry. Some recreational facilities were also created in northern Wisconsin but these were more common in the southern part of the state. Devil’s Lake State Park, Wyalusing State Park, the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, the Arboretum in Madison, Rib Mountain State Park, and many other sites benefited from CCC efforts. Throughout its existence, the CCC in Wisconsin employed 92,000 men, 75,000 of whom were from Wisconsin, and paid out about $16.5 million to enrollees’ dependents.

Planting trees

Lunch in the field

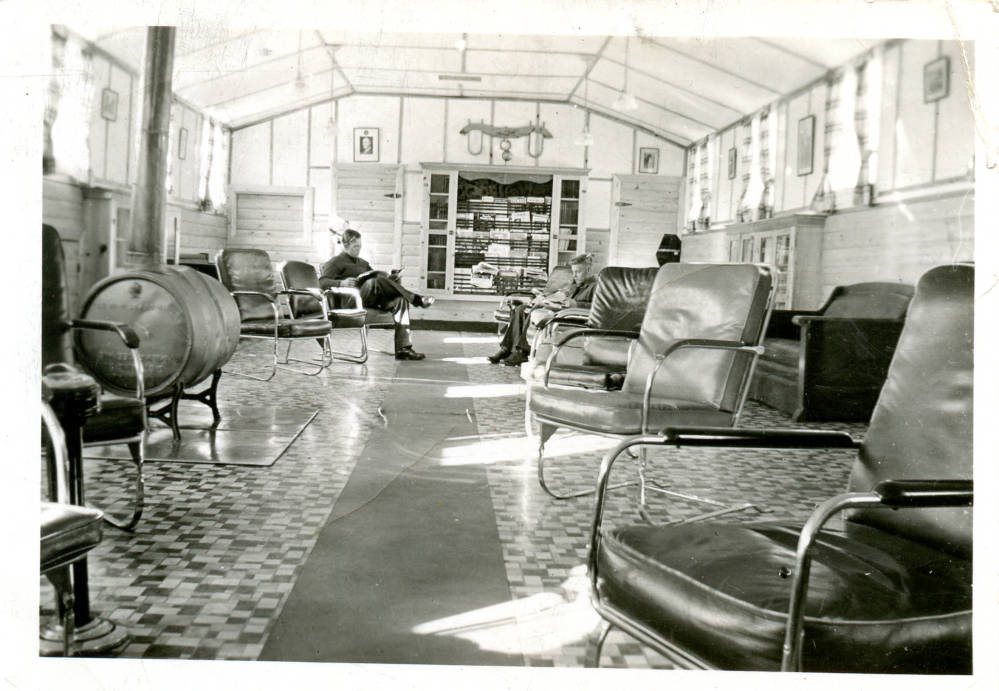

Reading room

Infrastructure

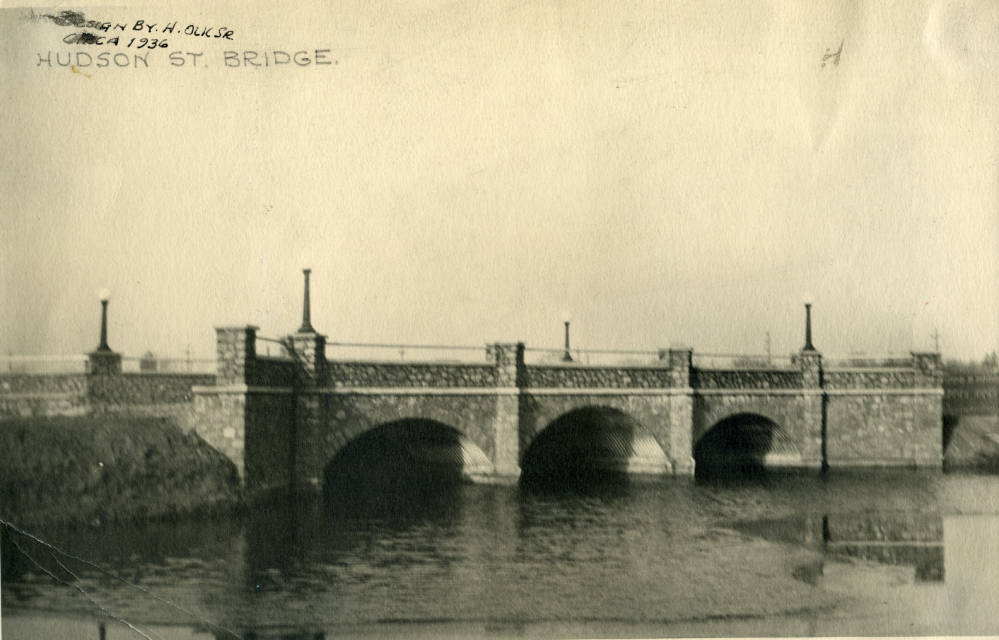

Infrastructural improvements in urban and rural settings were another major focus of the New Deal programs. Initially FDR set up the CWA as a short-term job creation program, primarily funding construction. It later became incorporated into the FERA which was set up by two of FDR’s advisors: Harry Hopkins, and Secretary of Labor Francis Perkins. Hopkins was made head of FERA with the charge of putting Americans to work. A separate division was set up for professional and non-construction projects. This included women doing such work as sanitation surveys, highways and parks beautification, public building renovation, public records surveys, and museum development. In 1935 FERA was replaced by the WPA which continued until 1943 when labor shortages no longer existed, in part because of the U.S. war effort.

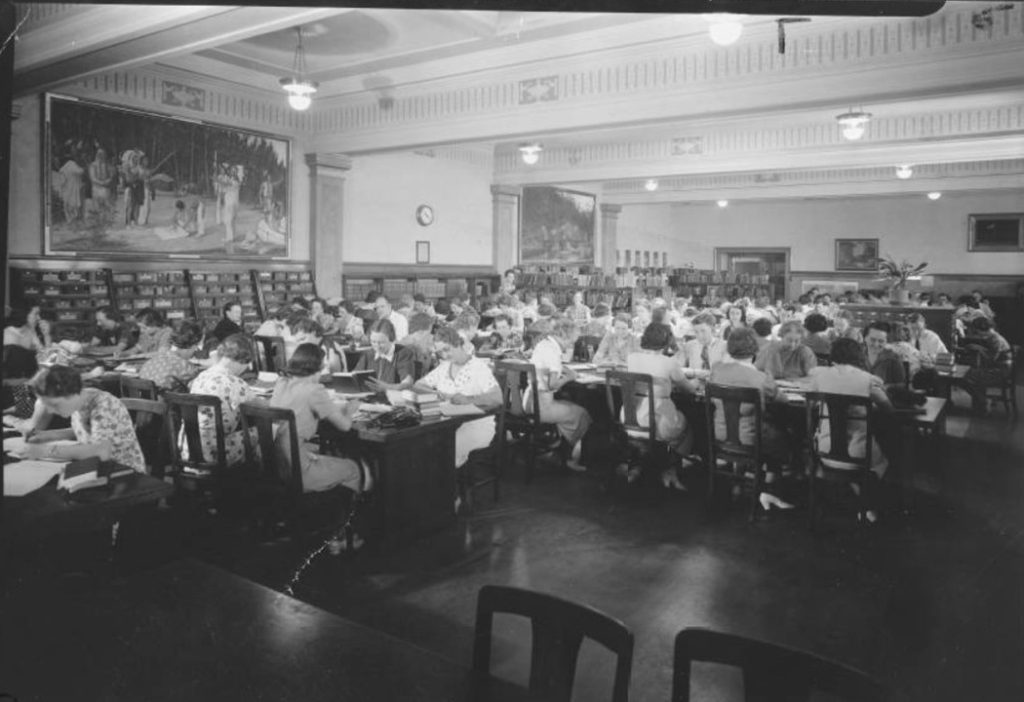

Almost every community in the U. S. had a bridge, school, park, or road built as a result of a New Deal Project. In Wisconsin, in 1935 alone, FERA employed about 2,800 college students as part of a student aid program. This enabled students to attend college who might not have been able to afford it. From 1933 to 1935, FERA allocated $77 million to construction projects (about $1.3 billion today).

By the time the WPA was disbanded it had created, nation-wide, 650,000 miles of roads, 78,000 bridges, 125,000 buildings, 800 airports built or improved, and 700 miles of airport runways. It served almost 900 million lunches to school children and operated 1,500 nursery schools.

The Arts

The WPA realized that it takes more than roads, bridges, and parks to form a rich life and so they also funded recreation programs and the arts. Recreational programs had three goals: employing persons possessing talent in the field of recreation, providing creative and recreative programs of constructive and worthwhile leisure activities, and developing community morale. Programs included those dedicated to athletics, social recreation, dramatics, arts & crafts, and music.

Nationally, in its lifespan, the WPA presented 225,000 concerts to audiences totaling 150 million, theater performances to 30 million people, and 475,000 works of art and at least 276 books and 701 pamphlets. One interesting project of the WPA Writers’ Project was a series of travel guides to each of the 48 states and Alaska.

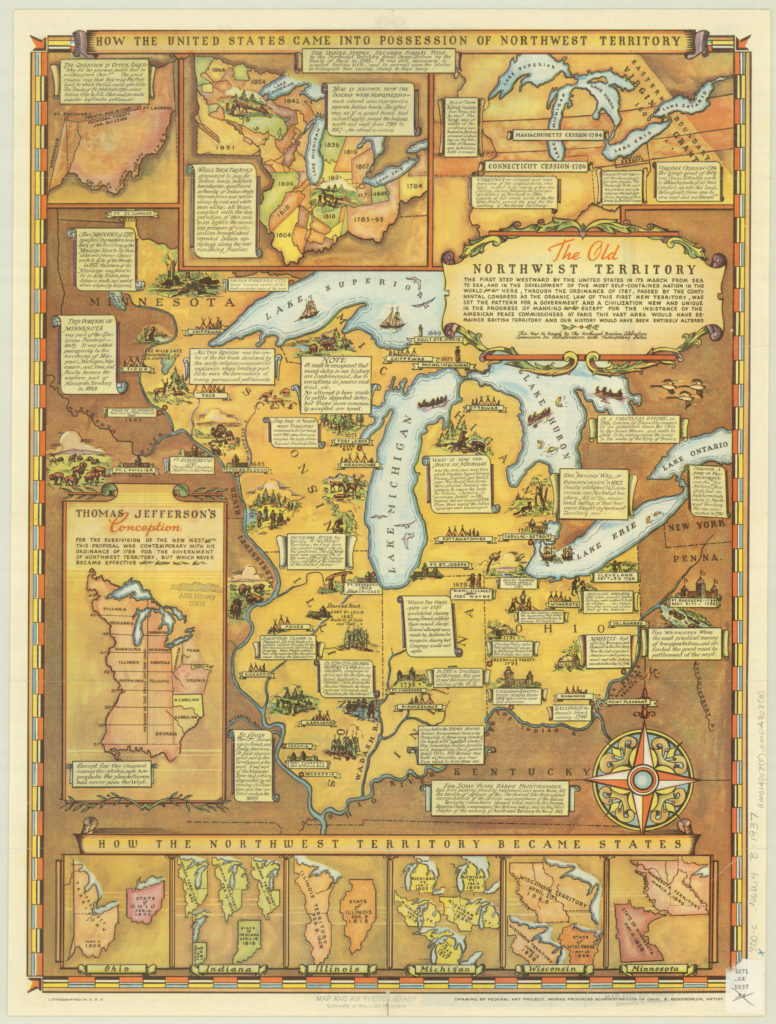

Motifs

Wisconsin Indian

place legends

Come and Sing:

Book of Songs

Epilogue

FDR’s collection of programs was unprecedented and played an important role in helping Americans recover from the Great Depression. In the 80 to 90 years since these programs were launched, we still benefit from the results through our parks, infrastructure, and restored natural surroundings. The success of FDR’s New Deal programs has also revised our outlook on the role of government in civic life.

Resources

- The WPA Federal Writers’ Project Guide to Wisconsin

- Carol Ahlgren, “The Civilian Conservation Corps and Wisconsin State Park Development” Wisconsin Magazine of History 71, 3 (1988): 184-204

- Perry H. Merril, Roosevelt’s Forest Army: A History of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942 (Montpelier,VT: P.H.Merrill,1981)

- Jerry Apps, The Civilian Conservation Corps in Wisconsin: Nature’s Army at Work (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2019)

- Explore the Elcho Civilian Conservation Corps Collection from Langlade County Historical Society

- The Civilian Conservation Corps: Camp 657 in Elcho (Langlade County Historical Society video, 27:14 minutes)

- Nick Taylor, American Made-The Enduring Legacy of the WPA: When FDR Put the Nation to Work (Bantam Books, 2009)

- John Zimm, editor, Blue Men & River Monsters, Folklore of the North: A WPA Collection, foreword by Michael Edmonds (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2014)

- Explore the Wisconsin Arts Projects of the WPA, 1935-1943 from UW-Milwaukee Libraries

- The Living New Deal

- CCC Legacy

- The Works Progress Administration (PBS)

- American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940 (Library of Congress)

- The Great Depression (PBS)

You must be logged in to post a comment.