Guest curator Terese Allen has written scores of articles and books about Wisconsin’s food traditions and culinary culture, including the award-winning titles The Flavor of Wisconsin and The Flavor of Wisconsin for Kids. She is food columnist for Edible Madison and Edible Door magazines, vice-president of the Culinary History Enthusiasts of Wisconsin (CHEW) and a longtime director of REAP Food Group, the cutting-edge food and sustainability organization based in Madison. Discover more of Terese’s work at tereseallen.com.

Along with cheese and beer, sausage is one of Wisconsin’s signature foods. An important foodstuff in the region for millennia, sausage dates back to the days of ancient Indians who made pemmican by mixing deer and other game with wild rice, corn, fat or berries, and stuffing the mixture into animal skins or shaping it into patties to be smoked.

The area’s fertile lands provided copious wild game and—eventually—domesticated livestock for settlers from Europe who had their own traditions of sausage-making. Indeed, nineteenth-century immigration from Germany, Bohemia, Poland and other “link-loving” regions was a principal force in the growth of Wisconsin’s culture of sausage. Each ethnic group that came here brought old-world recipes and methods that—along with the nation’s regional favorites plus specialties from new American cuisine—formed today’s wide-ranging selection.

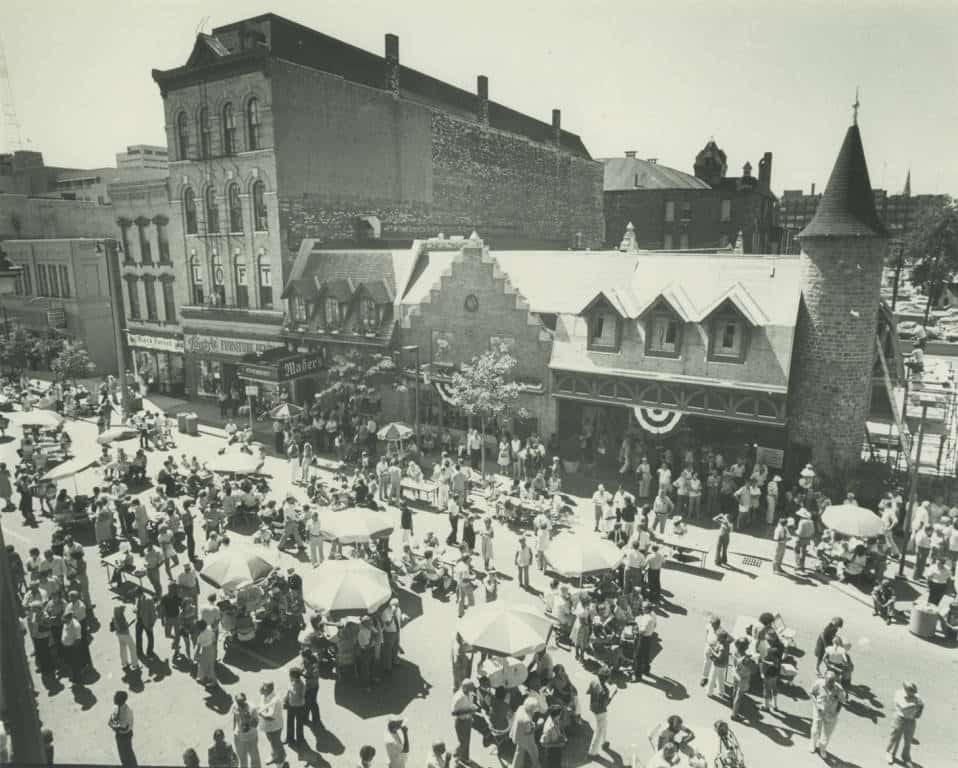

Wherever immigrants settled, particularly Germans in the Milwaukee region, they opened butcher shops which drew crowds eager for a taste of the old country. Shop-owners made Bavarian bratwurst, Bohemian jaternice and dozens of others. The many ethnic groups that populated Wisconsin in later decades added more flavors to the mix: Italian soppressata, Mexican chorizo, Albanian cevapcici and many more. Some, like the Belgian trippe of the lower Door County-Green Bay area, remained local favorites, while bratwurst went on to become a state icon.

Forging Links

Wisconsin’s rural settlers did their own butchering; this took place during the fall and was a hectic, demanding time. Families used almost every part of the animal to create edible links, and nearly every member got into the sausage-making action.

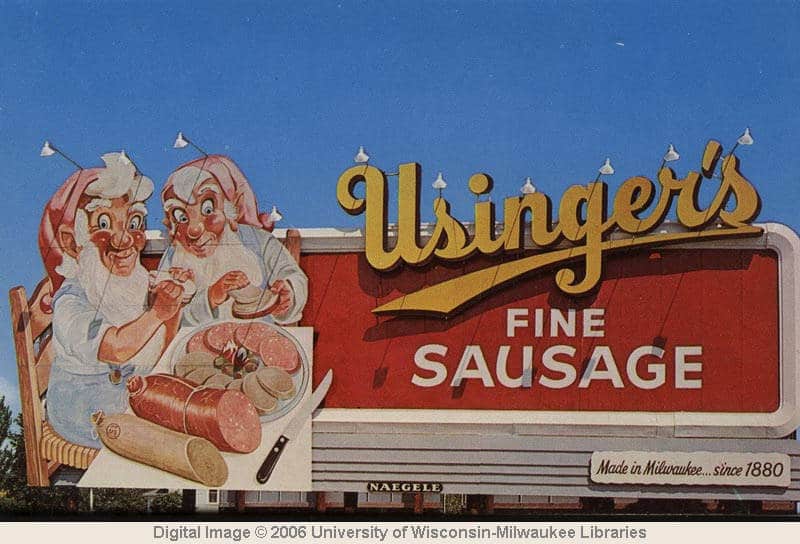

City dwellers depended on local butcher shops to supply them with both fresh and processed meats. Some urban sausage-makers later became major players in the meatpacking industry. Usinger’s of Milwaukee, for example, was started in 1880 by an apprentice sausage maker from Frankfurt. In 1919, Chicago butcher Oscar Mayer opened a meatpacking plant in Madison that eventually became—and continued for decades as—the company’s headquarters.

Wisconsin remains home today to many small, specialty meat markets; they’ve outlived sweeping changes in the meat industry in part because of the deep-rooted tradition of sausage making and the continued presence of small farms that supply local meat for processing. Butcher shops also have support from another Wisconsin legacy—deer hunting. Custom venison processing is big business to small shops; some work from November into late spring processing thousands of pounds of venison sausage annually.

In very recent times, the rise of the farm-to-table movement has given the state of sausage yet one more boost. In Madison, for example, Underground Meats is one of several new nose-to-tail butcher shops that market unusual, hand-crafted charcuterie, including fennel-y finocchiona and ‘nduja, a fiery, spreadable smoked salami made with roasted peppers. Conscious Carnivore offers hands-on sausage-making classes that include a sausage feast at the end of the lesson. On the Madison restaurant scene, the chefs at Heritage, Osteria Papavero and Steenbock on Orchard, among others, break down whole hogs to create everything from upscale linguica to old-timey head cheese.

Best Wurst

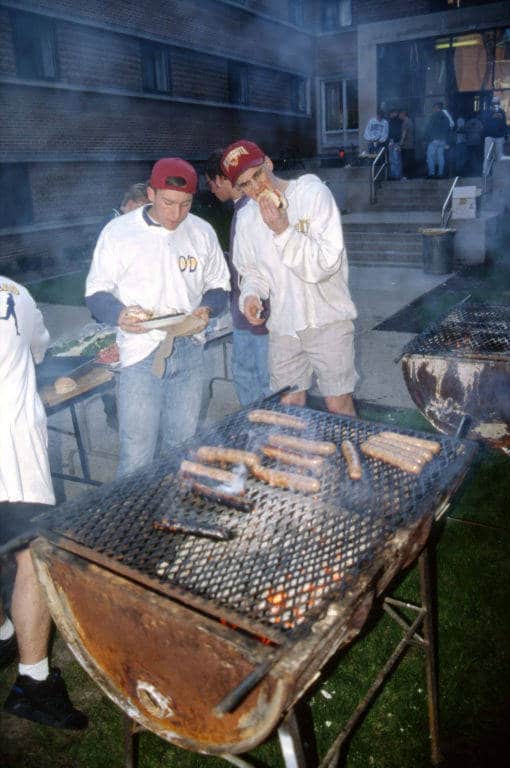

Old or new, there is one sausage that stands out in the crowd. Bratwurst – king of the links, core of the cook-out, Wisconsin’s very own soul food. The birthright of early German immigrants who substituted easier-to-find pork for the veal in traditional sausage, bratwurst illustrates how traditional foodways survive by adapting to new surroundings. Wisconsinites enjoy beer-soaked, flame-kissed brats at fraternity picnics, church suppers, Green Bay Packers tailgate parties, community festivals and county fairs. As Joseph Kapler Jr. wrote in “On Wisconsin Icons” for the Wisconsin Magazine of History, “The brat is for the most part present anytime two or more Wisconsinites get together and there is outdoor cooking involved.”

Sources

The images in this online exhibit come from the following digital collections. Click the links to browse the full collections.

- Building a Campus, Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries

- Eau Claire Area Historical Photographs, Chippewa Valley Museum

- Greetings from Milwaukee: Selections from the Thomas and Jean Ross Bliffert Postcard Collection, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries

- Milwaukee Historic Photos, Milwaukee Public Library

- Skare Collection, McFarland Historical Society

- Turning Points in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society

You must be logged in to post a comment.