The guest curators for this post are Nick Hoffman and Jesse Gant. Nick is the curator at the History Museum at the Castle in Appleton and Jesse is a Ph.D. candidate in history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Together they are writing an introductory book-length history of 19th century bicycling culture in Wisconsin for the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. Wheel Fever: How Wisconsin Became a Great Bicycling State will be released in Fall 2013.

“All Hail the Velocipede”

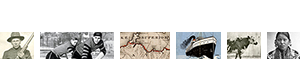

During the winter of 1869, the velocipede—the forerunner of today’s modern bicycle—first arrived in Wisconsin as a form of indoor entertainment for middle to upper class residents. First designed in France by Pierre Lallement, velocipedes were made of wooden frames and iron components. With poor outdoor conditions, traveling salesmen opened indoor velocipede rinks where novice spectators could try to ride a machine or watch professional stunt riders. By spring 1869, downtown streets in communities like Milwaukee, Appleton, Oshkosh, and Eau Claire reported velocipedestrian sightings. Parlor songs and newspaper cartoons, such as this clipping from Harpers Weekly, celebrated the contraption, but unfortunately for the velocipede, many critics helped end the passing fad.

Preachers, Workers, and Fighters

Bicyclists united in the League of American Wheelmen to organize for cyclist’s rights and to create a sense of community among membership. Formed in 1880, the organization was sometimes progressive in admitting both men and women, but rarely extended membership to non-whites, ultimately ruling against racial integration. The organization was most active in mid-sized to large cities like Oshkosh and Milwaukee, where local chapters organized bicycling tours and races and advocated for local improvements like good roads through license taxes.

First published in Milwaukee in 1890, the Pneumatic served as the primary organ for the Wisconsin division of the L.A.W. by sharing information on new bicycle models, century rides, and gossip about popular bicycle racers. In particular, the magazine followed the career of Milwaukee’s Walter Sanger, who rose to international professional cycling prominence.

Extreme Tourists

Some of the most celebrated 19th century bicycling achievements involved amassing thousands of miles via extreme long distance touring. Bicycle travelers from North America and even Europe visited Wisconsin. Pittsburgh’s Frank Lenz traveled through Waukesha during his world tour that fatefully ended with his murder in Armenia in 1894. Albert Fleck from Hanover, Germany, visited Milwaukee in 1896 during a challenge by his hometown’s cycling club to pedal around the world. Wheelmen aided tourists by creating a state map and guide book that recommended safe routes with good road conditions, as well as consuls in each city that offered friendly hotels and restaurants.

T.P. Gaylord and Herbert Gates of Beloit are shown here in 1896, wearing ideal bicycling clothing next to their tandem, which is loaded with baggage for a short multi-day tour.

You can learn more about bicycle tourist Frank Lenz in David Herlihy’s The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of an American Adventurer and His Mysterious Disappearance.

Debating Bloomers

Bicycling provided women with new leisure opportunities and helped begin a fashion revolution. Despite the sport’s popularity with young women, society still discouraged their participation with information that claimed long-term health risks. In Appleton, Wisconsin, the first sight of a woman wearing a bloomer suit on city streets created tremendous controversy, because the clothing questioned socially constructed gender roles. Even state leaders like Belle Case La Follette discouraged bloomers and argued in favor of more conservative and traditional clothing.

Most women bicyclists, however, still wore long dresses, such as Augusta Wilhelmy, who is shown riding a pneumatic bicycle at her family’s farm near Manitowoc, Wisconsin. Women’s bicycle models protected skirts with covered gear shafts and rear wheel netting that blocked clothing from getting caught in the chain and spokes.

Bicycle Boom

Wisconsin’s bicycling population grew by the thousands during the 1890s. The oversaturated market drove prices down and made the machine affordable to working class men and women. The increasing demand for bicycles spurred a massive growth of bicycle, bicycle parts, and sundry manufacturing companies in American cities. Southeast Wisconsin boasted new factories like Sterling (shown here), Andrae, Sercombe-Bolte, and Meiselbach, which hired hundreds of men, women, and children who made handlebars, pedals, and frames.

Bicycle factories were notorious for poor labor practices. Skilled male employees organized in the International Bicycle Workers Union and Allied Mechanics to fight for better working hours and conditions. Bicycle activists encouraged workers to ride to their factory shifts and hoped the bicycle would launch a transportation revolution, freeing humankind from the burdensome and sometimes unreliable horse.

Bicycles Influence the Rise of Automobiles

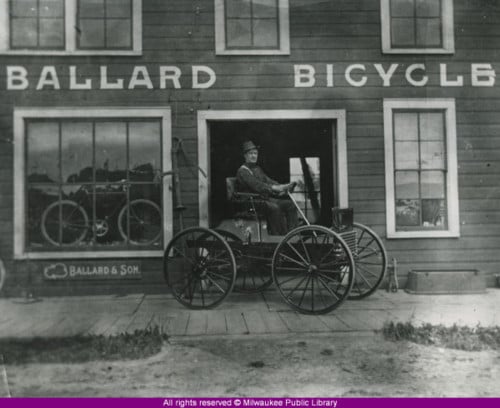

By the mid 1890s, the League of American Wheelmen were focusing their activism on the Good Roads Movement. Led by Milwaukee attorney Otto Dorner, the Wheelmen began a massive publicity campaign to persuade Wisconsin’s rural residents to support the construction of a modern road system. Farmers were discouraged by the proposition of city-dwellers cycling through their neighborhoods and feared the tax burden for roadways would fall on their shoulders. Progressive Wheelmen found compromise with farmers by developing a funding balance between townships, counties, and state aid. The construction of new roads coincided with the rise of automobiles, and many bicycle racers and manufacturers shifted to this new technology. Even small businesses like Ballard’s Bicycle in Oshkosh began testing horseless carriages as the bicycle’s popularity waned as the model form of transportation.

Sources

The images in this post come from the following digital collections. Click the links to browse the full collections.

- C. E. Dewey Lantern Slide Collection and Louis Thiers Glass Negative Collection, Kenosha History Center. From the digital collection Kenosha County History: Images and Texts, 1830s-1940s, part of the State of Wisconsin Collection from University of Wisconsin Digital Collections

- Herbert Gaytes Collection, Beloit College Archives

- Manitowoc Local History Collection, Manitowoc Public Library. Part of the State of Wisconsin Collection from UWDC

- Milwaukee Historic Photos, Milwaukee Public Library

- Turning Points in Wisconsin History, Wisconsin Historical Society

You must be logged in to post a comment.