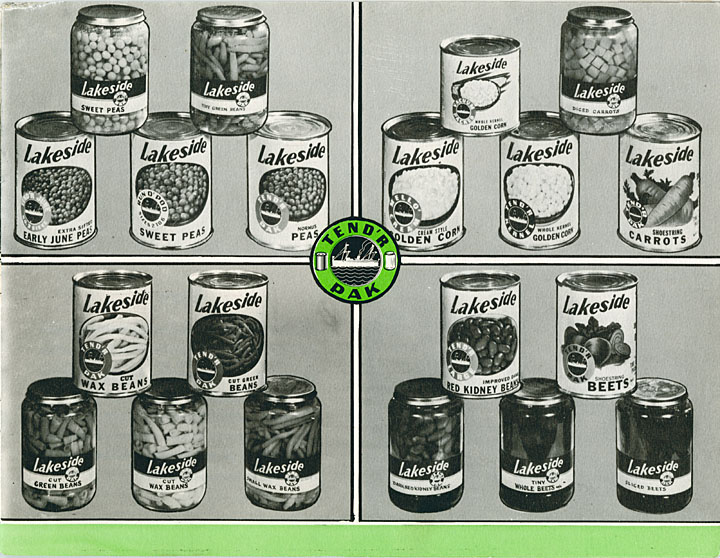

The story of commercial canning in Wisconsin turns out to be the story of the pea. The canning of beets, corn, cucumbers and other crops has been an important part of Wisconsin industry since the late 1800s. However, it was a native Pennsylvanian and his peas that started it all. The first commercial canning operation in Wisconsin (and the first east of the Appalachians) was founded by Albert Landreth in Manitowoc in 1883, to commercially can his farm’s peas. With $10,000 in capitol and 120 acres of peas, the Landreth Company was born. It later became Lakeside Packing Company and still exists today as Lakeside Foods.

Manitowoc Public Library

Hear Lakeside Packing Company employee Gordon Lund discuss the history of the company, including its use of POWs for labor during WWII, the migrant workforce, and OSHA regulations, in his 1976 oral history interview from the Manitowoc Public Library

Commercial canning was an effective way to increase crop demands, benefiting farmers across Wisconsin. A Bureau of Business Research and Service report published in 1948 noted that “the canning industry spread outward over the state, first to the south and west and later to the north and west, avoiding the sandy central area.” By 1920, Wisconsin was packing half of the nation’s total crop of canning vegetables. For those looking for an excellent piece of Badger State trivia, according to the same report, Wisconsin was “the leading pea-canning state in the nation.”

The number of Wisconsin canneries peaked in 1931 at 170 canneries, many of them one-plant companies. Canneries could be found in Onalaska, Cambria, Horicon, and many, many other locations.

Onalaska Public Library and Onalaska Area Historical Society

Cambria-Friesland Historical Society and Jane Morgan Memorial Library

Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey

While commercial canning was a boon for many, it was apparently a bust for others. Dr. T. E. Loope wrote in the Annual Report of the Wisconsin State Horticultural Society in 1908:

“I want to say this, that a great many places in the country have canning plants that they would be willing to part with, cheap, and the reason is that some promoter comes along and tells the farmers some fairy stories about what can be done, tells about the great profits and about how easy it is to get the products put up and everything of that kind. They omit one thing and that is, you have to have capital behind the product and not a little capital, not merely capital sufficient to erect the plant and get the necessary machinery and building and the like, but you have to have more if you are going to be successful.”

By the 1940s it was more difficult for small canneries to stay in business as commercial canning operations began to consolidate and multi-plant canneries become more prevalent.

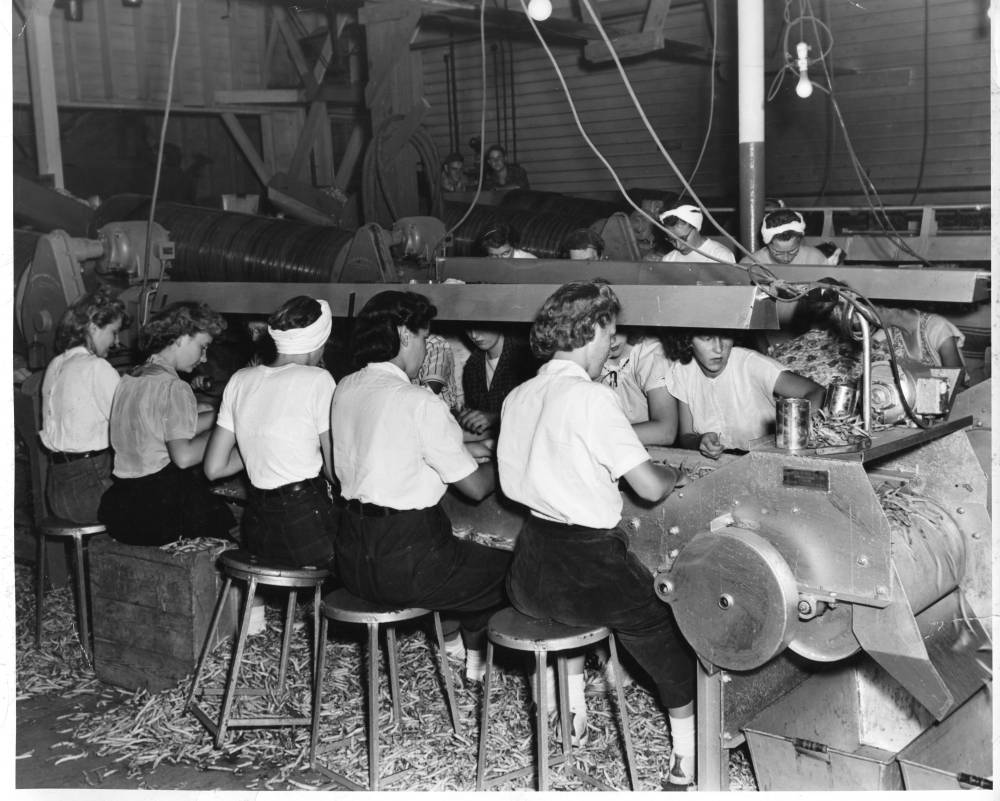

Women often canned in their homes, but they were also part of the commercial canning workforce. They performed any number of jobs, including office work, picking, sorting and inspecting. Much of the work was seasonal. For example, according to a 1913 report from the Industrial Commission of Wisconsin, pea canning, on average, had an employment season that was just 29 days long.

West Salem Public Library and West Salem Historical Society

South Wood County Historical Corporation

The demand for cannery workers increased during World War II. More food needed to be canned and shipped to support troops and of course the workforce had been depleted as men entered the Armed Forces. German prisoners of war imprisoned in Manitowoc worked in the fields and in canneries. The Lakeside Packing Company used their labor for two seasons, and several other canning companies in Saukville, West Bend and Belgium used POW labor as well. After the war the prisoners were shipped back to Germany.

“During World War II when there was a labor shortage, the cannery was running day and night. To get extra workers, the officers arranged for twenty German prisoners of war to work the night shift. They were being held in Marshfield and were brought to Athens by bus every evening.”

Athens, Wisconsin Centennial, 1890-1990

Lester Public Library

An essay on commercial canneries in Wisconsin would not be complete without acknowledging the impact of migrant labor on the industry. Starting in the 1920s and 30s, Wisconsin agriculture and the commercial canning industry turned toward Spanish-speaking migrant workers, most from Texas, to complete harvests and to can the goods for commercial sales.

As historian Sergio González, author of Mexicans in Wisconsin (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2017) describes in a lecture recorded for Wisconsin Public Television:

“Following the expansive agricultural dive of World War II, the number of Wisconsin crops raised and harvested for canning leapt upward . . . farmers were responsible for hundreds of thousands of acres of field with peas, sweet corn, cucumbers for pickles, cherries, snap peas, lima beans, sugar beets and tomatoes. And who did these farmers turn to for migrant work? People from Texas. Growers and canners concentrated the recruitment efforts on these Texas-born, Mexican-American families, also known as Tejanos.”

“Wisconsin agriculture depends on the 12,000 migrants who come here each year to tend, harvest and process certain farm and orchard crops, as we do not have enough people in the state when we need them.”

“Report on Survey of Services and Facilities for Migrant Workers Employed by Wisconsin Canners,” Wisconsin Canning Association, 1953

Mauston Public Library and Juneau County Historical Society

While Wisconsin no longer accounts for half the production of canned goods in the U.S., the canning industry is still important. According to the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison/Extension, the industry provided about 4,800 jobs and paid labor income (wages, salary and proprietor income) of about $293 million with about $2.5 billion in industrial sales in 2014. That’s a pretty big “peas” of the economic pie.

You must be logged in to post a comment.