Some of our favorite Wisconsin food traditions owe their origin to our state’s Indigenous and immigrant communities. Relying on oral tradition, beloved recipe books, local ingredients and a little ingenuity, generations of cooks created, transformed, and passed down these beloved dishes, often shared at ceremonial or holiday gatherings, community meals or local eateries. Over time, they have simply become part of our state’s food culture, the mere mention of any eliciting murmurs of “Mmm, (fill in your favorite dish)!” and inspiring a spontaneous dash to the closest market for ingredients.

But what about brats or cheese curds or cream puffs, you ask? This menu is by no means complete – consider it a sampler plate, so to speak. Bon appétit!

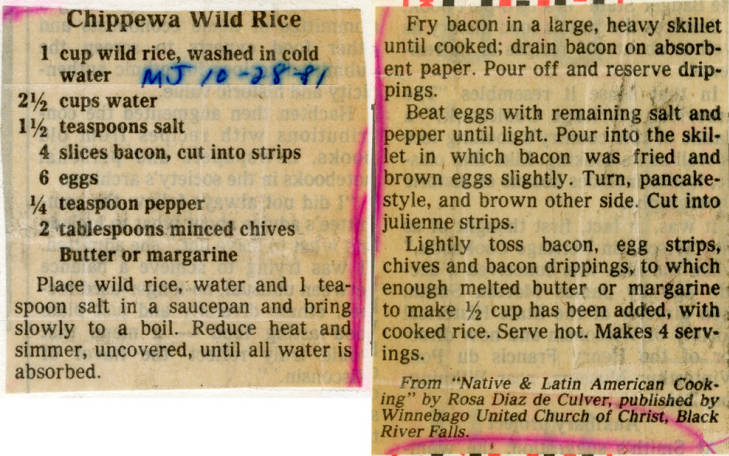

Wild Rice

In Ojibwe, Minwanjigewin means “to eat something that tastes good and is good for you” which perfectly describes our first dish. Known as manoomin or “the good berry” in Ojibwe, wild rice has long been a staple of the Indigenous diet and enjoyed during ceremonial gatherings. According to oral tradition, centuries ago during their long migration from the East coast, the Ojibwe were instructed to find the place where “the food grows on the water.” This ultimately led them to the shores of Lake Superior and the northern inland lakes of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota where manoomin grew in abundance.

UW Digital Collections Center

Traditional methods used by the Ojibwe people to harvest manoomin or “knock the rice” are still used today and inspire annual summer gatherings. In August, Ojibwe moved to their manoomin camps for the labor-intensive but highly social and ceremonial harvest activities. Harvesters use canoe paddles to access manoomin beds, wielding long poles to expertly maneuver through the rice beds. Traditional forked “push poles” are crafted for mobility and safety. These 16-foot poles provide canoe stability while preventing damage to the wild rice stands. Ricing sticks or “knockers” are used to thresh or bump the kernels into the canoe. The sticks are made from a lightweight wood and measure about three feet in length. The sticks are held in each hand, allowing the harvester to reach to the side and pull rice stalks into the canoe and knock the kernels into the bottom of the canoe.

Logan Museum of Anthropology, Beloit College

Wild rice is actually an aquatic grass. Considered a divine gift, manoomin has long been a vital part the Ojibwe diet. This high-protein, low-fat super food does not require pre-soaking and triples in bulk when cooked. Additionally, the uncooked rice can be stored for long periods of time. This grain is distinguished from other rice for its nutty taste and interesting texture. Served hot or cold, it is commonly used in meat and vegetable casseroles, soups, pancakes, muffins or as a dressing with turkey.

Milwaukee Public Library Digital Collections

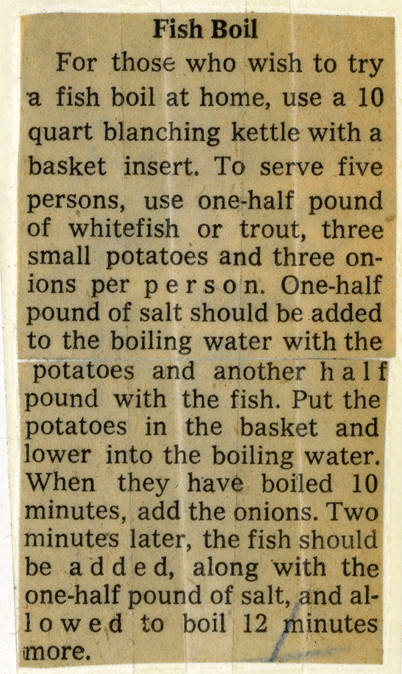

Fish Boil

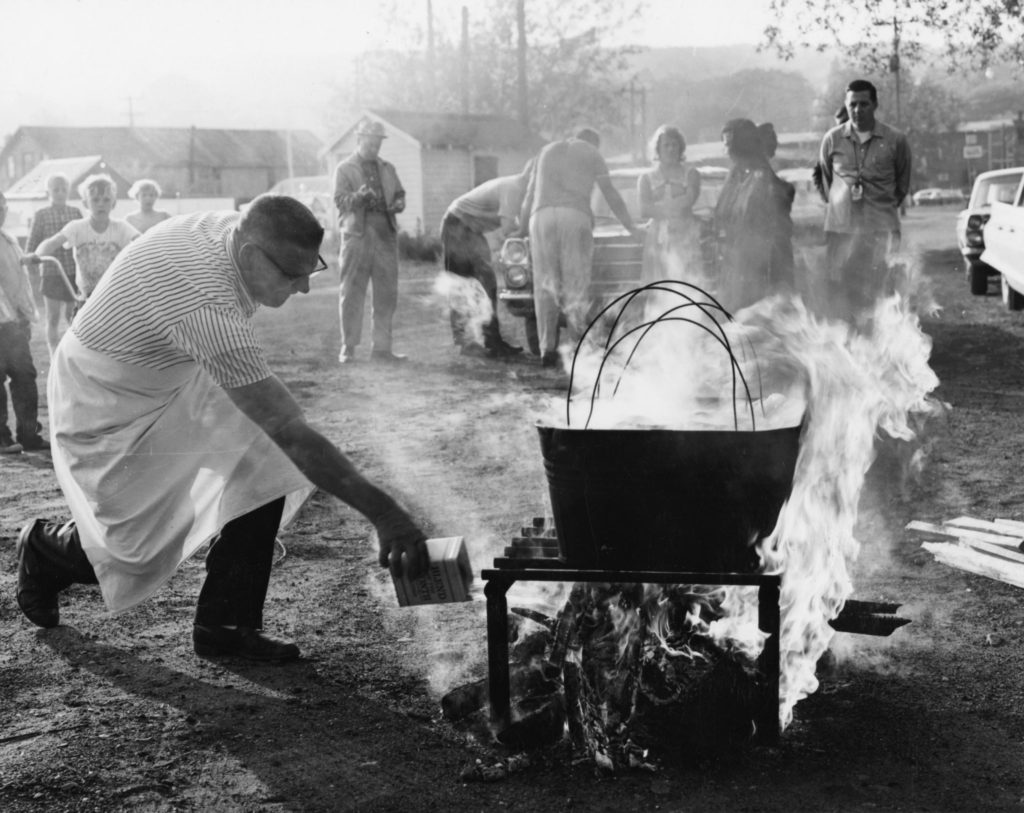

This Great Lakes culinary tradition is a source of pride within the Door County region of Wisconsin. Generally held outdoors in a community-style kitchen, a fish boil is prepared in a cast iron kettle over a wood fire. Fishing and proximity to streams, rivers and the Great Lakes provided sustenance for area Indigenous communities and Scandinavian immigrants who arrived in the 1800s. At its core, a fish boil is a relatively simple way to provide nutrition for large groups of people while supplying a valuable byproduct – fat and grease – used for cooking and healing.

The ingredients are simple: a half a pound of salt per gallon of water, red potatoes, quartered onions, and Lake Michigan or Lake Superior whitefish. The vegetables and fish cooked separately in two wire baskets.

Like a circus ringmaster, a boil master not only directs cooking but also entertains spectators during the process, sharing stories, telling jokes and narrating the cooking process, which can vary depending on the size of the kettle. The highlight of this event is the “boil over.” As oil from the boiling ingredients rises to the surface, the boil master throws a dash of kerosene under the pot causing a showstopping fireball which forces the grease, oil, and water over the pot’s edges and onto the ground, leaving clean, “lean” fish.

It’s not just a meal, it’s community-experienced performance art! Visitors flock to Door County each summer to experience this tradition. Fish boil is typically served with melted butter, lemon wedges, coleslaw or salad, bread, and a slice of fresh-baked Door County cherry pie.

Milwaukee Public Library Digital Collections

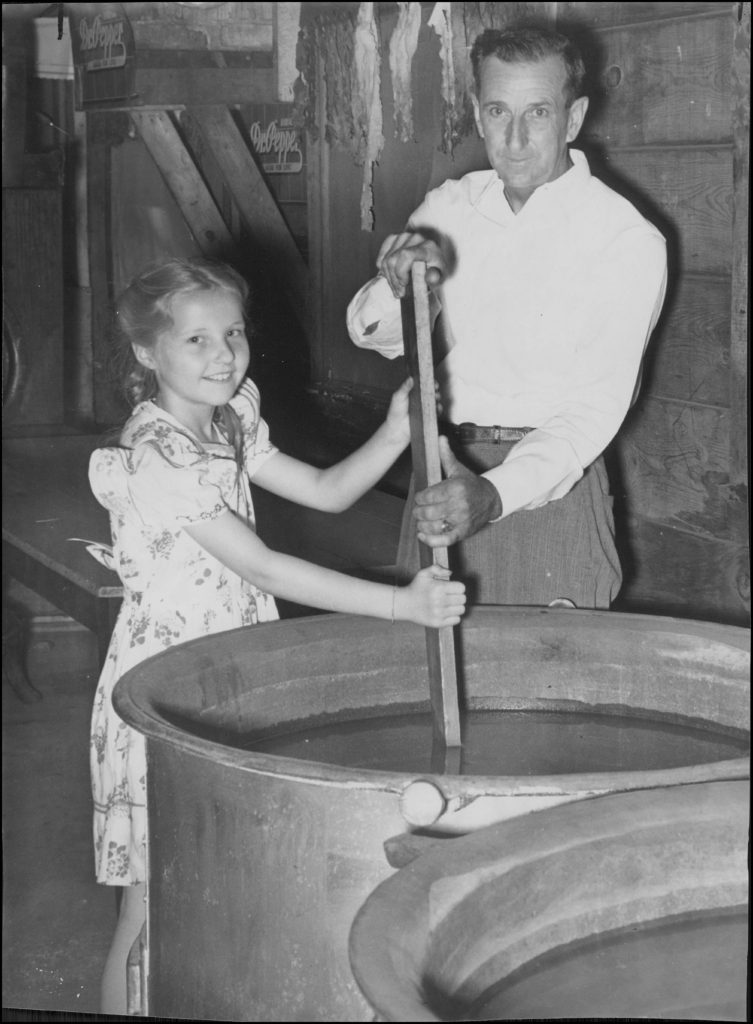

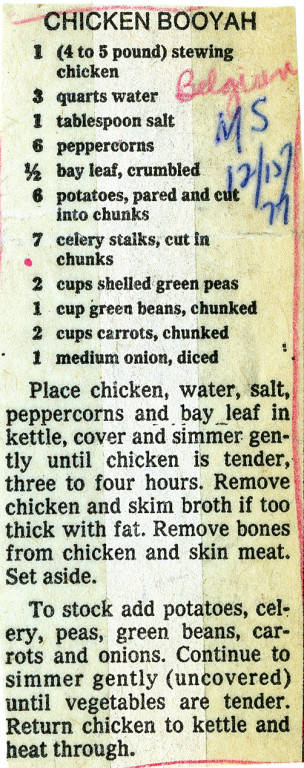

Booyah

It’s fun to say, even better to eat! Pronounced “BOO-yah,” this thick stew is popular throughout the upper Midwest but in northeastern Wisconsin in particular. A fall food tradition, booyah is both the event and the dish served at said event – “Come to my booyah for booyah!” Belgian French-speaking Walloon immigrants lay claim to this tasty dish. Arriving mostly in the 1850s, Wisconsin’s Belgian immigrants were the largest Belgian rural settlement in the United States. They settled in a tightly packed length of woods between Green Bay and Sturgeon Bay.

So, what exactly is booyah? The Dictionary of American Regional English attributes the name to French Canadian Walloon pronunciation of bouillir (to boil) and bouillon (broth) although others claim the name comes from the French seafood dish, bouillabaisse. Over the past century, more than one Green Bay family claims an ancestor responsible for inventing the dish and tradition.

Whether brought over from Belgium or simply evolved in northern Wisconsin by Belgian immigrants over subsequent generations, booyah is a hearty soup or stew that can take up to two days to cook. It is traditionally prepared outdoors in specially designed “booyah kettles” made of steel or cast iron to endure long periods of intense heat, with some holding up to 50 gallons of stew.

of booyah, 1946.

Minneapolis Newspaper Photograph Collection, Hennepin County Library Digital Collections

A good booyah is all about ingredients and timing. It begins with a bone broth made from short ribs, chicken and/or oxtails, prepared at least a day in advance. Before dawn on “booyah morning,” the stew is prepared outdoors over a wood-burning fire starting with the broth, dried beans, onions, garlic, and meats. Throughout the day, additional ingredients are added at hourly or two-hour intervals and may include cabbage, carrots, celery, rutabaga, peppers, and potatoes. Some recipes call for canned peas, and corn.

Milwaukee Public Library

Digital Collections

This dish is so adored, in 2019, the Northwoods League collegiate summer baseball team in Green Bay, Wisconsin renamed themselves the Green Bay Booyah. It comes as no surprise that one can enjoy a quart of booyah while cheering for the Booyah!

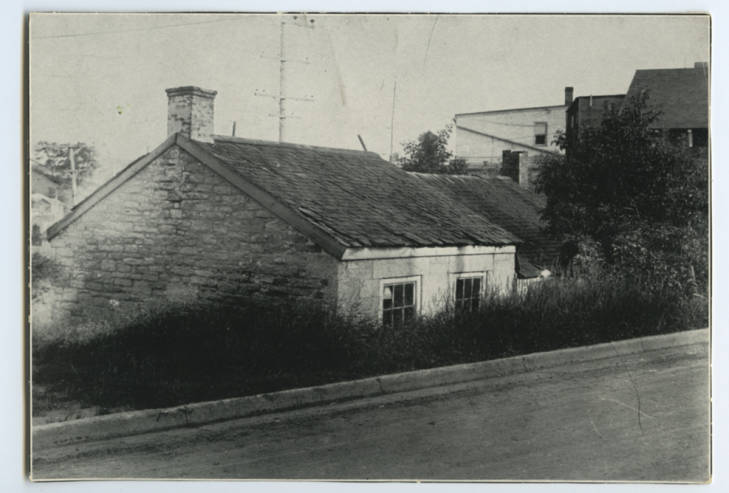

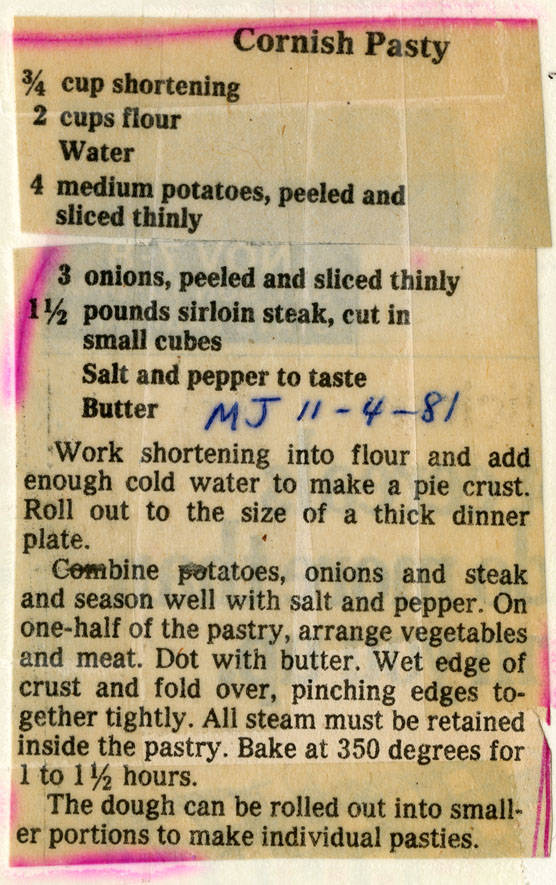

Pasty

PAHST-EE (sounds like past, not paste) is a pocket-sized meat and vegetable pie that found its way to our state by way of Cornish miners immigrating to southwest Wisconsin in the 1830s. They arrived from Cornwall in southwestern England and settled primarily in Mineral Point which developed into a lead and zinc-mining center during the 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1845, roughly half the town population claimed Cornish ancestry.

Mineral Point Library Archives

Also known as Cornish pasties, these baked and savory pastries are simple to create. To begin, place uncooked filling on one half of a pastry dough circle. Fold it in half to wrap the filling and crimp the curved edge to form a tight seal before baking. Voilà! You have a pasty! Typical fillings include beef, onions, carrots, turnips, potatoes, and rutabagas. Traditional pasties were small and easy to transport and store. The thick crust retains heat, keeping the pastry warm until lunch time, making them popular with workers. Pasties provided a hearty and high-calorie meal, much-needed substance for those engaged in extreme physical labor.

The Cornish Pastry Association requires the following to be deemed a “genuine” Cornish pasty: a minimum 12.5% meat and 25% vegetable; no meat other than beef and no vegetable other than potatoes, turnips and onion; all ingredients much be uncooked upon assembly and slow baked; and, if the crust is not crimped, it’s not a Cornish pasty.

Milwaukee Public Library Digital Collections

Mineral Point continues to celebrate its Cornish heritage at the annual Cornish Festival which includes a “Taste of Mineral Point” and ample pasty consumption.

Works Consulted

These resources were used to research this exhibit and provide further information on the Wisconsin delicacies discussed above.

- Minwanjigenwin: Food and Tradition

- The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary

- Manoomin-Wild Rice: The Good Berry

- Door County, Wisconsin’s iconic fish boils are history in a cauldron by Chris Chamberlain, foodrepublic.com (Nov 2016)

- Upper Great Lakes fish boil – a tasty tradition, Minnesota Sea Grant

- Fish boils in Door County, Door County Visitor Bureau

- Wisconsin Pioneer Experience

- Belgian-American Research Collection

- Rivers of booyah all flow toward one man by Paul Srubas, Green Bay Press Gazette (Jan 2016)

- Pasty, Wisconsin 101 (Our History in Objects)

- Cornish Pasty Association

- Mineral Point Library Archives Collection

You must be logged in to post a comment.